♦

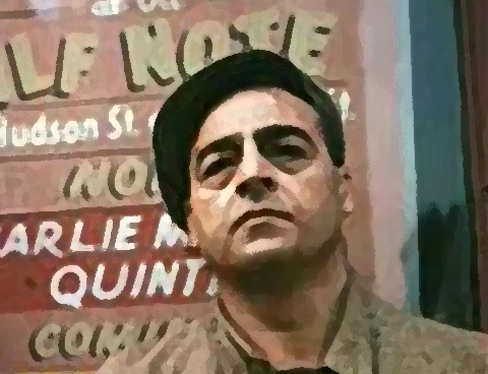

I. Eric Mottram: A Fortnightly Dossier, compiled by Simon Collings.

A Notebook of Materials Made under Stress.

As editor of Poetry Review (1971–77), Eric Mottram played a major role in introducing British audiences to what was happening in American poetry, wrote a pioneering book on Allen Ginsberg, and authored the first critical study on William S. Burroughs, with whom he became acquainted during Burroughs’ time in London. With contributions by Clive Bush, Jeff Hilson, Stephen McGarty and Allen Fisher, an excerpt from his ‘Kent Journal’ and a selection of previously unpublished work.

II. Catherine by Lucian Staiano-Daniels.

A war story a poem. ‘When I was dead, it was before the walls of Turin. When I was alive, it was even so. Nata song in Prague thirty first 8ober 1582, at one minute after half past one in the morning. When I was fourteen I became a man. I went to the wars in Flanders and the wars in France. I served the King of Spain…I died under the walls of Turin at two in the morning on fourteenth Xember. It was the year of God 1640, and I was fifty eight years old.’

Also in The Fortnightly Review: The Lay of Love and Death of Christoph Cornet Rilke von Langenau, by Ranier Maria Rilke, translated by Harry Guest.

‘Dylan smashed the form of the popular song. He broke the expected rubric….His standards have not merely a universality, but also a transportability, that makes them a ceaselessly moveable feast. Jazzmen can take them on, spin them round, and turn them into pyrotechnic riffs. You can sing them a capella in the car. They can survive the sentimental maulings of drunks near midnight. In evolutionary terms, his songs are survivors.’

More by Alan Wall: Birthing the Minotaur, Of Entropy and Knees, The Tramp’s Companion.

‘People saw the UFOs that began appearing in the mid-twentieth century as majestic light-radiating structures, shy aerial saucers, derby-shaped entities, triangles, cigars, or cylinders. The most typical popular response to them resembles the one voiced after airline pilots and others saw a UFO hovering above O’Hare International Airport in November 2006. Had extraterrestrials blown into the Windy City?’

More by James Gallant: On Bodily States and Intelligence, The Octogenarian Mattress-Mind.

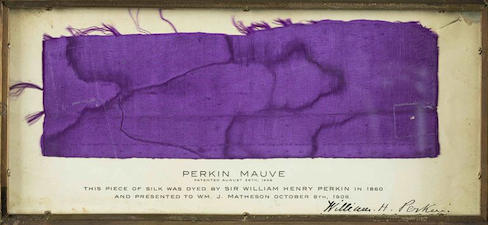

V. Blue by Daniel Coyle.

‘The color of distance and desire, loss and longing, heartbreak and heartache. Photographers call twilight the “blue hour” — a time for moody shots and long exposures when blue light from an unseen source sates the air, washes over everything softly enough to pull you in, cool enough to push you away, like the one who seemed to pursue you years ago, only to refuse you.’

More by Daniel Coyle: Yellow.

VI. Making Mordor: two views, by Jonathan Gorvett and Anthony Howell.

An Iliad, where the only heroes are Trojans: As the rage of Vladimir Putin is unleashed on Ukraine, two Fortnightly writers examine the reasons for his anger and violence and the consequences of waging war over injured pride. This is the century’s first truly Homeric conflict. It may not be the last.

Martyrdom by Anthony Howell.

We need to talk about Vladimir by Jonathan Gorvett.

VII. The Loves of Marina Tsvetaeva by C.D.C. Reeve.

The real world is not the world our senses reveal. For the ones dead in that world are alive—really alive—in that other world: the world of love. The departed—the ones who have left us—are still here, never really having left at all. In a letter, Marina Tsvetaeva tells her Czech friend that when she heard of Sonechka’s death, she ‘descended into that eternal well where everything is always alive.’

Published with Khlystovki, by Marina Tsvetaeva, newly translated by Inessa B. Fishbeyn and C. D. C. Reeve, and six poems by Sophia Parnok, in translations by Alex Chernova, Anna Ivaskevica and Alex Wong.

VIII. Violet by John Wilkinson.

VIII. Violet by John Wilkinson.

‘With Eliot’s poem The Waste Land, the violet hour recurs as the eventide bringing into sharp and estranged focus, activities and settings which otherwise are banal; they become endowed with significance in the way a carefully-framed black-and-white shot of a bedsit becomes emblematic of a life’s shrinkage – unless captioned as the home of an artist who would go on to become famous, or had notoriously endured neglect or “reduced circumstances”’.

IX. Keats, Beyond the Pleasure Principle by Nigel Wheale.

IX. Keats, Beyond the Pleasure Principle by Nigel Wheale.

‘After the horrors of the First World War, Sigmund Freud felt compelled to draw back from his detailed, psychoanalytic practice and reflect on his discoveries at a higher, more abstracted level. He termed this his ‘metapsychology’, and its most remarkable expression is Beyond the Pleasure Principle. This text provides a fascinating commentary on the psychological aspects of John Keats’ poetry, and life.’

X. Lamentations by Igor Webb.

X. Lamentations by Igor Webb.

‘Matthias’ “Some of Her Things” is a courtly threnody for lost time, as though Arnaut Daniel had taken up prose. It recalls Berryman’s “Dream Songs” also insofar as its great effort to hold steady, to hold things together, to write subjects after verbs, intermittently breaks down, and a manic or unmoored association kidnaps the writing.’

Published with ‘Some of Her Things’, by John Matthias, and ‘Everything that is the case,’ a review by Peter Robinson.

XI. The Right Side of the Diamond by Peter Knobler.

XI. The Right Side of the Diamond by Peter Knobler.

‘Matthew Carlyle had played softball pretty much all his life. In a T-shirt and jeans, in sweatpants, in double-knit polyester league uniforms with sanitary socks. He’d been a hot shortstop, one of those thin, quick boys with soft hands and a strong arm who covered a lot of ground. He was no longer any of those. As Matt had grown older he had simply refused to stop playing….’

XII. Robert Desnos and Lewis Warsh by David Rosenberg.

‘In 2020, his last year on earth, Lewis Warsh told me he’d reread his 47-year-old translation of Robert Desnos’s Night of Loveless Nights, and was startled by its tonic relevance to late life. We were twenty-somethings when we took the French avant-garde poets in the 1920s, from Max Jacob to Pierre Reverdy, as our forefathers of deadpan, no less than Louis Armstrong: it was the decade in which American jazz riveted Paris.’

XIII. The Last Apocalypse by Peter Riley.

XIII. The Last Apocalypse by Peter Riley.

‘The two beacons of apocalypse are of course Dylan Thomas and W.S. Graham, both deeply engaged with poeticised language at its most evasive, Thomas grappling with sense, Graham with language. Thomas was in many ways the original when in 1933, to quote Keery, “A poem in a sports journal by a provincial teenager, sent shock waves through literary London – acclaim which, as William Empson noted, ‘does some credit to the town’”.’

XIV. Brodsky’s Travels: Leningrad to Venice by Jeffrey Meyers.

XIV. Brodsky’s Travels: Leningrad to Venice by Jeffrey Meyers.

‘Once sent into exile, Brodsky, charged with curiosity and energy, became a wanderer and a cunning Ulysses. His travels were at once a flight to freedom and quest for inspiration, a synthesis of history and direct experience. His response to a new city and its culture was a means of self-exploration and self-revelation.’

XV. The Seicento and the Cult of Images by Yves Bonnefoy.

XV. The Seicento and the Cult of Images by Yves Bonnefoy.

‘Here the mouths breathe, the blood circulates; the painter has eyes only for life, for its warmth and its liberation from all forms. What seduced him in this instance was the vast sexual force that courses through Creation, where it has often been perceived as one of the consequences of Original Sin.’ Translated by Hoyt Rogers.

Published to accompany Bonnefoy’s essay, one by Rogers: ‘Seeing with Words: Yves Bonnefoy and the Seicento.’

Also: Bibliographic Archæology in Cairo by Raphael Rubinstein.

In the early decades of the last century, Egypt was home to ‘a remarkable collection of temporary residents, survivors from the shipwreck of modernity, scrambling and hustling, hiding out, stuck, or making the most of a good thing as long as it lasts’. Like its coastal twin, Alexandria, pre-war Cairo was a polyglot metropolis, ‘cosmopolitan yet also ruthlessly exploited and riven with profound levels of inequality’. Art critic Raphael Rubinstein surveys the scattered artifacts of an exotic literary backwater.

Women down the well by Natalia Ginzburg.

Women down the well by Natalia Ginzburg.

‘Women have a bad habit: they sometimes fall down a well; they are seized by a horrid sense of melancholia, drown in it, and struggle to come back to the surface. This is the real problem afflicting women…I have met so many women, and now I always find something worthy of commiseration in every single one of them, some kind of trouble, kept more or less secret, and more or less big: the tendency to fall down the well and find there a chance for suffering, which men do not know about.’ First English-language translation by Nicoletta Asciuto.

George Maciunas and Fluxus by Simon Collings.

George Maciunas and Fluxus by Simon Collings.

‘Drawing a clear boundary around Fluxus is, as many commentators have noted, an impossible task. Maciunas’ international network of Fluxus collaborators included musicians, visual artists, film-makers and writers, many of them experimenting with mixed media forms. Most of the artists had a life beyond Fluxus, and practices diverged significantly.’

♦

And… Tintoretto at 500 by Hoyt Rogers and Michele Casagrande.

Tintoretto at 500 by Hoyt Rogers and Michele Casagrande.

On the fifth centennial of Tintoretto’s birth, marked by exhibitions in Venice and Washington (through 7 July 2019), Hoyt Rogers reflects on the artist’s work and what it has meant to him. ‘Of all painters,’ he writes, ‘Tintoretto is the most Janus-like; he resumes the entire Renaissance, but he also looks forward to the future.’

This article appears in the portfolio ‘Tintoretto and Venice,’ which includes an essay by Michele Casagrande and a cycle of poems by Rogers.

Leaving Sidi Bou Said by Lorand Gaspar.

‘Do you know Sidi Bou Said? There are perhaps only a few dozen places in our world where such a miraculous masterpiece took place, born of an interaction between the mind and the experience of the men of an era, their skills, as well as the complex nature of the site itself…’ A visit to a former home by the French poet and essayist. With photographs by the author.

Prose poetry lost and found by Ian Seed.

A personal reflection: ‘I was impressed by what could be achieved in so few words. And finally, there was the fact that this was called a “poem”, but in terms of shape it did not resemble any of the poetry that I was studying at school, although I had read and enjoyed Blake’s Marriage of Heaven and Hell, which I had picked out on my own from the school library. Blake was in fact an important figure for Patchen.’ Also in The Fortnightly: Anthony Howell inquires: ‘The Prose Poem: What the hell is it?’

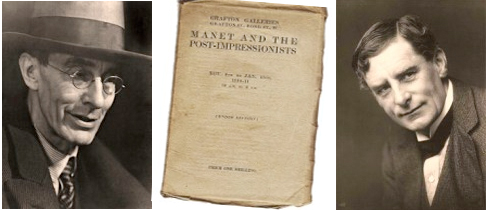

Roger Fry and the formalist project by Marnin Young.

Roger Fry and the formalist project by Marnin Young.

For painter Walter Sickert (right), the so-called Post-Impressionists are united only by their wilful “deformation” and violations of “quality,” but Roger Fry’s formalism owned the future. Both wrote about the 1910-11 Grafton exhibition for The Fortnightly Review. ‘The difference between the two texts, republished here, is about as good a demonstration as one could find of an intellectual watershed.’

and… Thoughts on Germany by Orson Welles.

and… Thoughts on Germany by Orson Welles.

‘You’d journeyed down from Berlin, and, in a break in the journey, you’d come upon this real, live munitions maker. There he was, with a flower in his button-hole, an Argentine girl at his side, a respectful ring of Swiss bankers all about him, smoking an Havana cigar on the borders of an Italian lake. The eyes in the sharply drawn, solid-looking head, are set in a questing expression. They are the eyes of a shrewd hunter, but you surprise in them a curious pallid emptiness—a dead spot. It is as though the centre of a target were painted white, or like the vacuum in the heart of a tornado.’

And not least… Walter Benjamin and the City by Alan Wall.

And not least… Walter Benjamin and the City by Alan Wall.

‘In the modern city, Benjamin observed the decay of experience. Here, experience shallowed out and speeded up…Continuities were fractured. Holistic representation shattered into montage, a kaleidoscope of impressions hammering away at the sensorium. It is impossible to draw an isometric section of modernity, because it will not stop moving long enough for the measurements to be made.’

For more, see the right-hand column. →

• •

.

Edited by Denis Boyles and Alan Macfarlane.

Poetry Editors: Robert Archambeau (US) and Peter Robinson (UK).

Associate editor: Katie Lehman.

♦

Editors, Contributors, and Contact Details.

. .

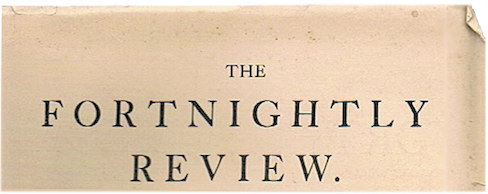

Editorial Statement.

The object of THE FORTNIGHTLY REVIEW is to become the organ of the unbiassed expression of many and various minds on topics of general interest in Politics, Literature, Philosophy, Science, and Art. Each contribution will have the gravity of an avowed responsibility. Each contributor, in giving his name, will not only give an earnest of his sincerity, but will claim the privilege of perfect freedom of opinion, unbiassed by the opinions of the Editor or of fellow contributors….We do not disguise from ourselves the difficulties of our task. Even with the best aid from contributors, we shall at first have to contend against the impatience of readers at the advocacy of opinions which they disapprove.

– Prospectus, G.H. Lewes, May 13, 1865. Emphasis added.

♦

Welcome to The Fortnightly Review. This is the New Series.

Click here for the Partial Archive of this New Series.

♦

List of Editors & Contributors.

Chronicle & Notices: Our Rolling Register of Shorter Articles, Excerpts from Interesting Books, and Notes from Elsewhere on the Web.

www.fortnightlyreview.co.uk. This site: © 2009-2023 The Fortnightly Review. All rights reserved.

The content of this website is the property of the individual authors and may not be reproduced or distributed without their permission.

Contact: info@fortnightlyreview.co.uk