< chapters 9 & 10 chapters 13 & 14 >

A Fortnightly Serial.

By ALAN WALL.

•

Chapter Eleven.

Messages

WILL GOT BACK to his flat on the Sunday and saw the red light flicking on and off on the telephone. He hoped it would be Sian.

WILL GOT BACK to his flat on the Sunday and saw the red light flicking on and off on the telephone. He hoped it would be Sian.

‘It’s Paul.’

That was it. Will played it over again. When he keyed in 1471 he was told that the caller had not left a number. Finally he phoned Sian, but there was no reply. He had bought her an answerphone for Christmas. It remained in its box under her table. The following morning he was on the train to Mercia College.

Jessica left early. She had to go to work. Charlie lay in the bed and asked himself if he knew what he was doing. He didn’t seem to hear any answer so he went back to sleep. He hadn’t had much sleep in the night. It must have been 10.30 when Lindsey walked into the bedroom.

‘The door was open, Charlie. Had a good night?’ He had noticed at some point in the darkness that the light in the room at the very top of the big house had been on, and a figure had been standing in the window. Only then had it occurred to him to pull the curtains and switch off the bedside lamp.

‘Coffee? I could put the percolator on.’ And she left the room. Charlie closed his eyes again. Soon he heard gurgles as the water slapped and choked. When Lindsey came back she was carrying two cups. She brought one over to the bed and put it down on the table. Then she went back to the wicker chair and sat in it, picking up the large leather folder from the floor where she had left it.

‘Coffee? I could put the percolator on.’ And she left the room. Charlie closed his eyes again. Soon he heard gurgles as the water slapped and choked. When Lindsey came back she was carrying two cups. She brought one over to the bed and put it down on the table. Then she went back to the wicker chair and sat in it, picking up the large leather folder from the floor where she had left it.

‘How’s your thesis going, Charlie?’

‘Feel like singing it more than writing it.’

‘You sang well last night. Really beautiful.’ Her American accent had softened a little after so many years in England, but not that much. She took off her jacket. White silk blouse. Lindsey was a serious dresser.

‘It was writing a thesis that brought me here in the first place, did you know that?’

Somewhere amongst the bric-à-brac in Charlie’s attic of memories he thought perhaps he did know, but hadn’t ever considered it much. She never could have finished it. There was no Doctor before her name.

‘I came here to research a mysterious Jacobean drama. Came over from Arizona to go through the Fenshawe Archive a quarter century ago.’

And here it had been once more, a maypole fumbled back towards the upright position after Cromwell’s interregnum, out in the light again after its years of rustication and disgrace.

Charlie sat up in bed, making sure the white sheets were pulled around his middle. He was naked. He started sipping the scalding coffee. Lindsey smiled. She remembered the day when as a boy he’d stumbled into the room where she sat reading, a look of unfathomable perplexity on his face as he stared down towards the swelling that had mysteriously afflicted him. Here was the erection. It sometimes seemed to Lindsey that there was in truth only the one erection, hic et ubique. It expressed itself with minor variations throughout the endless ranks of men. Sometimes as a blessing, more often as a plague. They had no more responsibility for such visitations than they did for the arrival of the wind, that freelance spirit which bloweth where it listeth. And here it had been once more, a maypole fumbled back towards the upright position after Cromwell’s interregnum, out in the light again after its years of rustication and disgrace. Such a long time since its last appearance in Lindsey’s life, and this day it had come to rise from, of all things, a child who could not even pretend to connect it up with his psychology, let alone his soul; an erection without guile or deceit then, encumbered with no ulterior motive, only the self-worship of stiffening flesh, a foray into future explorations, a rehearsal. This hardened little member was a precocious exile from the ghostly country of desire. Maybe it had come to test if what they said was true: that in the kingdom of the blind the one-eyed monster is king.

She had taken him on her lap, had stroked the bewilderment from his face. How many years ago had that been? She had no notion whether he was enduring the same affliction today, let alone whether it might relate to her in any way. Not that erections needed to relate, of course. Proximity was their object, not correlation. Any port in a storm. She had seen them through the window in the night. It had evidently been a strenuous engagement. Poor Charlie must be worn out.

How much of female sex was a womanish need to take them between your legs and let them thrash their rage away, let that impossible desire of theirs explode as you held them tightly, held them firmly in place through the catastrophe of their fulfilment? My little drowning boy. Come down lower then and I’ll show you how fluently the mermaid moves; how the tides of our bodies obey the moon. How many acts of coition had been perpetrated thus down the years? Like the square root of minus one, this was an impossible number to calculate. But Lindsey had come to feel that a woman was always being a mother when she made love to a man, whether anything ever came out of her womb or not. Nothing had ever come out of hers, and now it never would. She looked at Charlie’s long black hair, even more beautiful than hers had ever been. She picked up her folder.

How much of female sex was a womanish need to take them between your legs and let them thrash their rage away, let that impossible desire of theirs explode as you held them tightly, held them firmly in place through the catastrophe of their fulfilment? My little drowning boy. Come down lower then and I’ll show you how fluently the mermaid moves; how the tides of our bodies obey the moon. How many acts of coition had been perpetrated thus down the years? Like the square root of minus one, this was an impossible number to calculate. But Lindsey had come to feel that a woman was always being a mother when she made love to a man, whether anything ever came out of her womb or not. Nothing had ever come out of hers, and now it never would. She looked at Charlie’s long black hair, even more beautiful than hers had ever been. She picked up her folder.

‘Take this as coming from one PhD student to another, Charlie. Let me explain what happened with my research. A bedroom tutorial: I always wanted to do one of those. Reckoned the pay per hour might be higher than normal educational rates.’

‘If you can make it last an hour,’ Charlie said from the bed.

‘I have a feeling that wouldn’t be too much of a problem with you, Charles. Have you ever wondered how I came to be here, though? This curious exotic creature from the US of A, who’s never quite fitted in to your family?’

‘I heard rumours.’

The sole reference related to an original holograph located at Ivory House, the seat of the Fenshawe family.

‘I came here from Arizona where I was researching seventeenth-century drama. I discovered a curious reference in a notebook held at the manuscript library to a work entitled Her Starre Occluded. Written by Thomas Deedes apparently. A work of an almost Shakespearean dimension according to the nineteenth-century source, but not extant in print. The sole reference related to an original holograph located at Ivory House, the seat of the Fenshawe family. I wrote to Ivory House and received a most cordial response from Alasdair Fenshawe, your grandaddy. He had a dim recollection of some family tradition, but said he was far too busy to do anything about it. His wife had only recently died. However, if I wished to come over he would give me the run of the library and I could attempt to locate the mysterious work myself. I was obviously a serious scholar at a serious institution. With the help of my supervisor I got a travel grant and two months later I was here.

‘Alasdair I have to say was utterly delightful. I’d never seen anywhere like this place before. He insisted after the first few nights of my staying in a hotel that I should stay here instead. There was plenty of room. He had to be down in London for much of the time because he was selling the company, planning to retire here and…well, I’ve never been sure what, exactly. I moved in. I spent from morning till night going through the library, which had not been properly catalogued and which was in a pretty chaotic state. Then I found it. It had fallen behind one of the bookshelves. Here it is.’ And Lindsey held up a very antiquated-looking manuscript book. ‘I don’t think I’ve ever had a more exciting day in my life than that one, Charlie. It seemed that I had in my hands a genuine Jacobean drama that had never been printed, and which one diarist in the nineteenth century had thought had Shakespearean dimensions. The stuff of which scholarly reputations are made. Do you mind if I smoke?’ Charlie shook his head and Lindsey took out a slender ivory cigarette holder, sole remnant of one of Fenshawe’s more popular lines. She lit up.![]() ‘You realise that’s an elephant’s trunk you have in your mouth, Lindsey?’

‘You realise that’s an elephant’s trunk you have in your mouth, Lindsey?’

‘I’ve had worse things in there, believe me. Now I’m going to test you, Charlie. I know you had a hard night — all that music you played us, I mean — but let’s see if your researcher’s mind is functioning. I’m going to read you a little bit of Her Starre Occluded. Tell me if anything strikes you.

The Onan seede he scattered at the tree’s roote

Where she had writhed, her fleshe scraped harde

Against the fretted barke where first the Serpente

Undulated, tracing his snaile-spermed jisme,

Tooke roote amidst the tares, sprouted blacke bloomes

Poisonous, bringing first oblivion then vomites.

Thus Love’s emetick Empire was announced.

‘A real turn-on, eh Charlie? Anything snag in that scholarly mind over there in the bedsheets.?’

‘I don’t have a scholarly mind. I have a blues singer’s mind, that’s part of the problem. What’s the date meant to be?’

‘Say around 1606.’

‘Just jism, that’s all.’

‘You’re a smart boy, Charlie. Indeed you are. Go on.’

‘It’s thought to be the origin of the word jazz. Part of my ethno-musicological studies. Thought to maybe mean…’

‘Don’t spare my feelings.’

‘Spunk.’

‘Exactly that. Spunk, combining the meaning of pluck with imperial connotations of semen scattered where the sun never sets. But why did you pick up on it?’

‘I wouldn’t have thought it would have been used like that so long ago.’

‘Well, I’d be happy enough to take you on as a student, because you’re right once more. Its first recorded usage in English according to the good old pre-jismatic OED is 1842. With a G: gism. It was seemingly used, ah God bless the Brits their constancy before all change and decay, in reference to horses. As in, does that stallion of yours have gism? Does he frisk when he canters, my lord?

‘But here it is in Thomas Deedes. Dated 1606, some two centuries and more before the lexicographers’ first noted occurrence. And spelt with a j too. Just like Satchmo ordered. Curious, no? Also curious the use of the word earthshine in this passage.

So sullied and dislustre’d she

Unmaidened quite, the small barque of her chastitie

O’erwhelmed into the Gulph. What left for him

To do but share her drowninge? Thus do the Merman

And his Mermaid Drab make their wet way

Through Eastcheape, its tide of human traffic

Huge crossed waves of dross; ill-starred, ill-favoured,

All natural earthshine gone from off their faces.

‘Do you ever do that, Charlie? Look at what’s behind the words?’

‘Now Shakespeare uses earthshine when describing the moon, but not like this — this implies the use of a telescope. Remember Galileo didn’t get to look through his until 1610, four years after this was written. Thomas Hariot had one, that’s for sure, over at Syon where the Earl of Northumberland occasionally stayed, when he wasn’t being an alchemist in the Tower. My excitement was beginning to turn into something close to alarm. I’d already spent over two months going through every page of this manuscript. Funny little bells had started ringing. And then one day I looked at what lay behind the words. Do you ever do that, Charlie? Look at what’s behind the words?’ She didn’t wait for a reply. ‘What was behind the words was paper. And there I discovered the funniest thing of all. This manuscript, so authentic looking in its secretary hand, had been written on a wove paper. Does that mean anything to you, Charlie?’ He shook his head. ‘Curiouser and curiouser, you see. Because wove paper was only invented towards the end of the eighteenth century. So unless our Thomas Deedes lived as long as Methusaleh…’

‘Her Starre Occluded is a forgery.’

‘My conclusion too. I began to twig that I’d been had. But why? I had to go back over my notes. The original diary relating to nineteenth-century London where I’d found the reference had been written by one Arlan Wigmore Fielding. Any bells, Charlie?’

‘The campanologists have fallen silent.’

‘It took a while for it to dawn, I must admit. I wasn’t in the best of spirits. I’d pursued the whole train of this thing for over six months. Maybe I didn’t want to face the facts. It was only then that I made a note to myself and turned the name into an acronym. AWF. These initials kept recurring throughout the library, but I hadn’t thought it relevant so I’d put it out of my mind. AWF was also the initials of your illustrious literary ancestor, Alfred Wilberforce Fenshawe. Now are there any bells?’

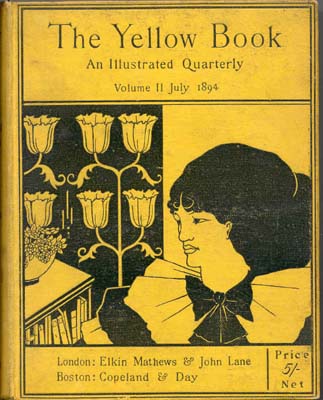

‘I’m hearing distant wind-chimes.’ They all knew something about him in the family. Alfred Wilberforce Fenshawe: a devotee of Swinburne. A great-great uncle, or something like that. Stories had circulated about him over the years. Charlie seemed to remember someone once saying that his biography should really be written one of these days, if anyone could ever find the time. He had composed strictly metred poetry of a classical hedonism, now almost entirely forgotten, though there were copies of his books about the house. He had appeared in The Yellow Book on a number of occasions. There had been several poems regarding flesh and pain, one of them illustrated with sadistic glee by Beardsley.

‘I’m hearing distant wind-chimes.’ They all knew something about him in the family. Alfred Wilberforce Fenshawe: a devotee of Swinburne. A great-great uncle, or something like that. Stories had circulated about him over the years. Charlie seemed to remember someone once saying that his biography should really be written one of these days, if anyone could ever find the time. He had composed strictly metred poetry of a classical hedonism, now almost entirely forgotten, though there were copies of his books about the house. He had appeared in The Yellow Book on a number of occasions. There had been several poems regarding flesh and pain, one of them illustrated with sadistic glee by Beardsley.

He was said to have been a friend for a while of Oscar Wilde (along with almost everyone else) though he didn’t share his proclivities, indeed expressed himself baffled at what Oscar had ever seen in it at all, but his own tastes were sordid enough. When he had any money he visited whores, preferably of the Parisian variety, vastly superior to the usual fare on offer in London, in his own well-informed opinion. As with cuisine, so with sex: those proud of what they offer you tend to pleasure you the more. The French had a sense that they were gifting you unaccountable graces, even if they were expensive, or had to be dispensed in a hurry; the English merely assumed they were assisting in your shame and penury by lifting two things out of your trousers at the same time.

‘I found myself going through his diaries, and they do make pretty interesting reading, Charlie, should you ever find yourself with a free evening, which doesn’t seem very likely at the moment, given your schedule. He did some winningly racy versions of Propertius. I even know a few lines by heart:

The way you’d dish the dirt

On all our neighbours from the living tomb

Before you laughed and threw your shirt

Across the whole length of the living room.

Why pay for what the weather supplies gratis, raining alike on the godly and the ungodly, that was Alfred’s line.

It was even rumoured that old Alfred had himself whipped for a while by naked Amazonians in a leafy garden in a north London suburb, but he soon got tired of that. Apart from anything else, he says the English climate is entirely unsuitable for such nude outdoor thrashings, since it already provides more than enough opportunities for masochism, fully clothed admittedly but still desolating, as the heavens weep and the northeasterlies howl, without having to search out such occasions on a voluntary basis. There was a practical side to old Alfred. Why pay for what the weather supplies gratis, raining alike on the godly and the ungodly, that was Alfred’s line. He had better things to spend his money on, mostly on the ungodly side, if the diaries are anything to go by. And if there was any beating to be done, Alfred undoubtedly liked to be the one wielding the cane. He liked his flesh raw at the moment of entry. There were plenty of candidates for this sort of thing between London and Paris at the time. But they did need paying. The only trouble was, the money ran out. His diaries are quite clear. Money was badly needed. And then I started to notice a funny parallel between some of Alfred’s preoccupations and some of the racier passages in Her Starre Occluded. How about these, Charlie?

He stript her to the pulp.

Its gleaminge white beneathe the barke

Moistened to his hotter touche…

Or this:

The vast bed though his second-beste

Afforded four carved lashing postes.’

‘Strong stuff for Jacobean England.’‘Isn’t it though. I don’t doubt they got up to it, and worse, but they’re not always so explicit in the plays. No problem being explicit about it all in Paris in the 1890s. Where a man might conceivably have heard the word jism. Things were just getting started. And then I discovered the reference to your ancestor in a letter that referred to him as an uncanny graphologist. Which in the context I took to be a less polite way of saying he was a gifted forger. And he was trying his hand at a bit of Jacobean pastiche, it seems. Pretty good it was too, I reckon. Fooled me for a while. But he was undoubtedly doing it for money. The market for Shakespeareana was growing.’

‘Strong stuff for Jacobean England.’‘Isn’t it though. I don’t doubt they got up to it, and worse, but they’re not always so explicit in the plays. No problem being explicit about it all in Paris in the 1890s. Where a man might conceivably have heard the word jism. Things were just getting started. And then I discovered the reference to your ancestor in a letter that referred to him as an uncanny graphologist. Which in the context I took to be a less polite way of saying he was a gifted forger. And he was trying his hand at a bit of Jacobean pastiche, it seems. Pretty good it was too, I reckon. Fooled me for a while. But he was undoubtedly doing it for money. The market for Shakespeareana was growing.’

‘So why didn’t he ever sell it?’

‘I reckon he was going to do that soon enough, having planted his trail of false clues, but then he died. In a slum in the East End where he was living with a whore. An English one, which must have irritated him. Diptheria. You were meant to destroy anything the infected person had been in touch with. Those were the rules. But someone from here obviously managed to get in and retrieve all his papers. For the sake of the family honour, maybe. By then he’d already been flogging off curious documents and planting leads for the sting that was to come. But death’s sting came first. And then the better part of a century later, it was my turn to get stung. By finding one of the documents he’d planted. My research went bankrupt. Six months up the Sewannee. Only one thing left to do, Charlie. Can you guess what?’

‘I reckon he was going to do that soon enough, having planted his trail of false clues, but then he died. In a slum in the East End where he was living with a whore. An English one, which must have irritated him. Diptheria. You were meant to destroy anything the infected person had been in touch with. Those were the rules. But someone from here obviously managed to get in and retrieve all his papers. For the sake of the family honour, maybe. By then he’d already been flogging off curious documents and planting leads for the sting that was to come. But death’s sting came first. And then the better part of a century later, it was my turn to get stung. By finding one of the documents he’d planted. My research went bankrupt. Six months up the Sewannee. Only one thing left to do, Charlie. Can you guess what?’

‘Marry grandad?’ She flinched at that and he was sorry he’d said it. She squeezed another cigarette into the ivory holder and lit it.

‘No, not yet. Not quite. I realised that the only thing I could retrieve from all the months I’d now spent on this, over in the States and then here, was to write a book about Alfred Wilberforce Fenshawe, the dissolute pagan hedonist. The only interesting part of my original thesis had just fallen through. So I put it to your grandfather. He said it could only be done after his death. Said he had made some sort of personal commitment on inheriting the family’s wealth and documents that he would keep Alfred quiet for another generation, so dark was his depravity, though these days I doubt it would stop him being appointed head of the BBC. I could work on it quietly, here, and publish once Alasdair was gone. And in the meantime, if I chose, I could marry him.’

There was silence in the bedroom. Raw sex had left it and something else had entered, but Charlie could not work out what it was.

‘So there you are, Charlie. Now you know the chronicle of how the horny bitch came over the Atlantic one day and stayed. Don’t believe everything you hear about me, by the way. Not all of those stories are true. And the reason I married your grandfather was because I came to love him, whatever other problems it might have solved in my life, and I grant you it did solve some. I loved him once, just like you do now. Never heard anyone speak the way he speaks, as though the dragon from the cave had eaten the dictionary and then spewed it all out in flames.

Sing me a song, Charlie, on that old guitar of yours. Something slow and sorry that sounds as if all the clocks have stopped in the Mississippi Delta.

And like Eve I was always seduced through the ear. Men are seduced through the eye, Charlie; women through the ear. He made me laugh. And he never gave a fuck about anyone or anything. In that respect at least he hasn’t changed at all.’ At the door she stopped. ‘Oh, by the way, there is a local legend that something in the air around these parts makes the girls particularly fecund about this time of year. Didn’t work for me, obviously. But you take care, Charlie, all the same.’

Then she called from outside through the window. ‘Come up to the house later, if you like. Sing me a song, Charlie, on that old guitar of yours. Something slow and sorry that sounds as if all the clocks have stopped in the Mississippi Delta. And I’ll feed you for your pains.’

§

Chapter Twelve.

Mercia College

THERE ARE TWO Os in the middle of the word philosopher, slap bang in the middle. Two little owl-eyes. Minerva the goddess of wisdom flies at twilight, according to Hegel. They could just be pools of vacancy, of course. Twin zeros. Or whirlpools where the world disappears and philosophy comes out in its place. Will wasn’t sure.

THERE ARE TWO Os in the middle of the word philosopher, slap bang in the middle. Two little owl-eyes. Minerva the goddess of wisdom flies at twilight, according to Hegel. They could just be pools of vacancy, of course. Twin zeros. Or whirlpools where the world disappears and philosophy comes out in its place. Will wasn’t sure.

He sat on the train and stared out of the window. Outside Birmingham there was a dumping-ground for defunct fridges. Thousands upon thousands of discarded coolers, off-white, mangled, their ice-cubes long melted, their CFC gases relinquished into the atmosphere, there to remain so as to help cook the planet towards its extinction. It would cool down in time, all the same.

A purple polythene bag had snagged in a single leafless tree. Above it a constellation of gulls swooped over a housing estate. Data accruing all about him in sinister patterns. A young woman sitting opposite, her face bony, the skin almost translucent, twitching and gawping with her own drug-induced mania. Each dilated eyeball an inferno of despair. Will could hardly bear to look but found it impossible to turn away. Finally she got off and he found himself staring at a hollow warehouse with bricked-up windows at the top of a weedy slope.

For a year or two there had been a curious mood of excitement which had always entirely baffled Will, because he never had much notion what was going on.

Beth Harding had taken over the college after a series of catastrophes. The good old extra-mural department had been reformed into an outreach centre, whose funding had become seriously confused. Into this serious confusion there came the bright ideology of private initiatives in higher education. It was in the air at the time, and this air penetrated the newly renamed Mercia College. For a year or two there had been a curious mood of excitement which had always entirely baffled Will, because he never had much notion what was going on. As it turned out, lots of other people hadn’t had much notion either, including a lot who should have done. And the new buildings, the new initiatives, the endless spawn of acronyms, a fresh poster at reception every Monday morning, all this had been based on the West Midlands’ own version of the South Sea Bubble. Will could still remember many of the revelations as they came out during the investigation.

A bible-reading class billed under comparative religion in fact consisted of a group of fundamentalist devotees who thought every word of the Good Book literally true and so filled and re-filled their diaries with freshly calculated dates for Armageddon. Their normal method of study was for a chosen reader to intone a scriptural text, interrupted every few verses by loud cries of Hallelluia and Praise the Lord. The inspectors couldn’t help but remark that the pedagogical methodology employed here might leave something to be desired, even according to the rather loose terms of Mercia College’s prospectus in those days. And they fared no better with Lifelong Creativity, one emaciated limb of the Community Outreach Programme, which it transpired took place in an old people’s home and consisted of a gerontocratic group, in various advanced stages of physical and mental decay, making the best stab they could at arranging paper flowers. When these sessions were completed, one of the carers would immediately throw the mess of knotted wood-pulp into the dustbin, making any long-term evaluation of the course’s effect somewhat problematical, and certainly throwing into question the £180,000 apparently assigned to it in the budget.

A bible-reading class billed under comparative religion in fact consisted of a group of fundamentalist devotees who thought every word of the Good Book literally true and so filled and re-filled their diaries with freshly calculated dates for Armageddon. Their normal method of study was for a chosen reader to intone a scriptural text, interrupted every few verses by loud cries of Hallelluia and Praise the Lord. The inspectors couldn’t help but remark that the pedagogical methodology employed here might leave something to be desired, even according to the rather loose terms of Mercia College’s prospectus in those days. And they fared no better with Lifelong Creativity, one emaciated limb of the Community Outreach Programme, which it transpired took place in an old people’s home and consisted of a gerontocratic group, in various advanced stages of physical and mental decay, making the best stab they could at arranging paper flowers. When these sessions were completed, one of the carers would immediately throw the mess of knotted wood-pulp into the dustbin, making any long-term evaluation of the course’s effect somewhat problematical, and certainly throwing into question the £180,000 apparently assigned to it in the budget.

Then there was the matter of foreign travel. The inspectors found it hard to understand the necessity of both the Principal and his Vice-Principal travelling together to Bermuda, Florida, California, Spain, Greece, Australia and the Bahamas at a total cost of £150,000 over a period of two years. They noted too that these trips invariably took place during the darker days of the lengthy West Midlands winter.

£28,000 had been assigned to a magazine entitled Model Building Mania, listed under the educational rubric Arts for Everyone. It didn’t take long for the inspectors to notice that the editor of this journal, Mark Rowland, happened to be the eighteen-year old son of the Vice-Principal, Vincent Rowland.

The £30,000 which had been allocated for ‘on-site computers’ could never be made to tally with any computers on any site the inspectors could locate.

Through all of this the college’s chosen auditors Roche Fairlie behaved with an insouciance verging on catalepsy. But then the inspectors one day registered that a different department of the same company was also picking up £120,000 per annum for consultancy fees. Unfortunately the inspectors were never able to fathom who had consulted whom about what; to what purpose; at what times, in which specified venues. On top of all this were the secretarial fees for secretaries who were never actually to manifest themselves in the flesh…but by then the game was already up.

Those students still blessed with the merest fraction of hope for humanity started staying away.

The Principal, the Vice-Principal and a considerable section of the Board of Governors promptly resigned, though not promptly enough to curtail police enquiries, which continued with varying degrees of vigour and attentivenes for some years. Given the number of uniforms along its corridors, Mercia College came to resemble more a war-time army barracks than a place of higher education. Will’s sense of oppression returned. His medication was increased. His estimation of the modern world and its educational provision, never very high to begin with, sank all the way down into the cellar of despondency. Life had become thoroughly dark once more. The philosophers he was prepared to discuss with his students were now limited to those whose gloom was of a preternatural reach and extent. Schopenhauer and Kierkegaard became particular favourites, along with Nietzsche. Those students still blessed with the merest fraction of hope for humanity started staying away.

But then Beth had been appointed and all of this was suddenly behind them. All they had to do now was to keep the students learning, keep the Centre turning. And all he had to do was to produce a CD-Rom on The Philosophy of Names for the Outreach Programme. The only trouble was, he didn’t have any notion how to do it. It struck him that he needed to have a word with Peter.

As he walked past reception Trish said, ‘Oh by the way, Will, Paul called.’ Will stopped and turned around.

‘Say that again.’

‘Paul called. Said you knew him.’

‘Did he leave a message?’

‘No.’

‘A number?’

‘No.’

Will walked up the stairs and down to the bottom of the corridor where Peter Lion’s room was. He knocked and walked in.

‘Hello Peter. Can I pick your brain?’

‘You’re welcome to anything you can find in there.’

‘Know anything about making CD-Roms?’

‘Do people still do those? I certainly don’t, but there’s someone around here who probably does. Just got some notes on it the other day. Hang on.’ He rummaged through piles of polythene files chaotically piled on his desk. ‘Yes, here it is. There’s one in preparation even as we speak. And the person doing it is…’ Peter looked up, his bright eyes even brighter than usual: ‘…you.’

•

Not surprising that in the songs about freight trains we shift from the lonesome whistle to the graveyard without taking breath.

UP IN SHEPHERD’S COTTAGE Charlie sat before his computer screen. So what’s the blues, then, the essence of the blues? He started tap-tapping on his keyboard. Death, drugs, booze, travel and women or, in Bessie Smith’s case, men. Death was always round the corner, often closely related to one of the other themes. Drugs, well you don’t need to have a PhD, not even one in ethno-musicology, to work out the connection there. Booze takes longer on the road to extinction and the instalments cost less, but amortized over a liftetime, you arrive at the same conclusion. There’s a terminus at the end of every line. Travel. It was usually by train, the arteries of the USA during the Depression and after. As it says in ‘Sitting on Top of the World,’ ‘Gonna catch me a freight train, Work done got hard.’ But travelling the lines was hard too. Those bluesmen didn’t go first class. In the freight wagons you were always waiting for the railroadman’s club, and if you were travelling the blinds, then it only took one false move and you were down on the tracks with the big wheels going over you. Not surprising that in the songs about freight trains we shift from the lonesome whistle to the graveyard without taking breath. The bottleneck and the harmonica make railroad sounds, the nearest you’ll ever get to the cold iron rails without actually sitting between them. Whistles, wheels turning, speed, danger, longing. The high metallic note of sadness, the lonesome cry of the big metal beast snorting steam, always in a hurry to be somewhere else.

They felt that death might have had a bad press, when you looked closely enough at life and its multiple downsides.

And as for women, you were either trying to get away from them or trying to chase after them, and they cost money too, more of it than you had, everything cost more money than you had. Money meant more lying and fighting and sometimes dying. Sudden death at least solved the multiple problems arising from the tangled world of romance: the songs pointed this out in the bitter precision of their throwaway lines — very practical people, blues singers. They felt that death might have had a bad press, when you looked closely enough at life and its multiple downsides. The blues stayed pretty unified, thematically speaking. The lovesheets at the song’s beginning are all too often shrouds by the end. And there’s religion when you die, of course, so some of them are spirituals too. The angels laid Louis Collins away, sang Mississippi John Hurt, but he did have to get himself shot first. Nothing’s free in the world of the blues: even your grave has to get paid for somehow. And then it will need to be maintained. As in life, so in death, hence Blind Lemon Jefferson’s plaintive plea: see that my grave is kept clean.

The blues singers even came to think of themselves in terms of the steam engine. Blind Lemon Jefferson once again said it for everyone: ‘Feel like a broke-down engine, I ain’t got no drivin’ wheel.’

There was only one truly significant white blues singer as far as Charlie was concerned: Bob Dylan. Other intelligent men of the age had played the blues, but none had brought all their intelligence, all the intelligence of the age, to bear upon it except for Dylan. No one but him had lived the blues the way the bluesmen did. No one but him had written a blues song about Blind Willie McTell, to Blind Willie McTell and called Blind Willie McTell.

You needed to have done a lot of hard thinking to write ‘Blind Willie McTell’.

There’d been no one else around with the resources to do it. To write so intelligently about the blues by the end of the twentieth century you needed to have read Rimbaud and the Kabbalah, meditated with the Buddha and seen Martin Luther King gunned down, as well as listening to all those old 78s. You needed to have contemplated the death of Elvis, and seen how fame metastasized and turned gargantuan, counted the footprints of men in white suits dancing on the moon, scrutinized the wreckage of your marriage and, last but not least, confronted the treacherous quality of money, its germinating malignancy in your mind, even as you peered inside the intimacy of your own battered wallet. You needed to have done a lot of hard thinking to write ‘Blind Willie McTell’. Dylan, so Charlie reckoned, had done as much hard thinking as anyone else in his time, as much as anyone in a university department, certainly as much as his dad. And he had more to show for it too. He had come away from the battle with some trophies. Just as articulate as Nietzsche, but a lot more tuneful. Songs. They beat books. With songs you were your own library.

Charlie closed down the laptop and reached for his guitar. He wondered if Jessica would come that night. He wasn’t sure whether he wanted her to or not. She did come, but that was the last time she came. In the morning he found a note with a telephone number and two words on it: Love Jess. He sat with the telephone in his hand that evening and thought about it. But he didn’t really know what to think about it, that was the truth. Didn’t seem much point asking his penis, though that had been the fellow making all the important decisions over the last few days. Maybe it was all too close to home and too risky.

That Friday he was back in London for his gig as Blind Charlie Shade.

♦

—This is the sixth installment of White Ivory. —

See previously

chapters 1 & 2

chapters 3 & 4

chapters 5 & 6

chapters 7 & 8

chapters 9 & 10

ALAN WALL was born in Bradford, studied English at Oxford, and lives in North Wales. He has published six novels and three collections of poetry, including Doctor Placebo. Jacob, a book written in verse and prose, was shortlisted for the Hawthornden Prize. His work has been translated into ten languages. He has published essays and reviews in many different periodicals including the Guardian, Spectator, The Times, Jewish Quarterly, Leonardo, PN Review, London Magazine, The Reader and Agenda. He was Royal Literary Fund Fellow in Writing at Warwick University and Liverpool John Moores and is currently Professor of Writing and Literature at the University of Chester and a contributing editor of The Fortnightly Review. His book Endtimes was published by Shearsman in 2013, and Badmouth, a novel, was published by Harbour Books in 2014. A collection of his essays was issued by Odd Volumes, The Fortnightly Review’s publishing imprint, also in 2014. A second collection, of his Fortnightly reflections on Walter Benjamin, followed in 2018, and a third collection, Midnight of the Sublime, has just been published. An archive of Alan Wall’s Fortnightly work is here.

ALAN WALL was born in Bradford, studied English at Oxford, and lives in North Wales. He has published six novels and three collections of poetry, including Doctor Placebo. Jacob, a book written in verse and prose, was shortlisted for the Hawthornden Prize. His work has been translated into ten languages. He has published essays and reviews in many different periodicals including the Guardian, Spectator, The Times, Jewish Quarterly, Leonardo, PN Review, London Magazine, The Reader and Agenda. He was Royal Literary Fund Fellow in Writing at Warwick University and Liverpool John Moores and is currently Professor of Writing and Literature at the University of Chester and a contributing editor of The Fortnightly Review. His book Endtimes was published by Shearsman in 2013, and Badmouth, a novel, was published by Harbour Books in 2014. A collection of his essays was issued by Odd Volumes, The Fortnightly Review’s publishing imprint, also in 2014. A second collection, of his Fortnightly reflections on Walter Benjamin, followed in 2018, and a third collection, Midnight of the Sublime, has just been published. An archive of Alan Wall’s Fortnightly work is here.

Image credits.

Flat vector two paper cups connected by string (Iryna Pasichnyk); two cups of coffee (loooby); mermaid print (Wikimedia Commons); cigarette holder, Auckland Museum (Wikimedia Commons); The Yellow Book (Wikimedia Commons); James VI of Scotland, I of England and Ireland (Wikimedia Commons); title page, Diptheria: Its Symptoms and Treatment (Wikimedia Commons); Owl of Minerva in Roman mythology, cropped from an ancient coin at the Numismatic Museum of Athens, Greece (Wikimedia Commons); Religious background – bright lightnings in red apocalyptic sky, judgement day, end of world (Ig0rZh); acoustic guitar with background removed (Irina Ashpina).

Post a Comment