< chapters 1 & 2 chapters 5 & 6 >

By ALAN WALL.

•

Chapter Three

The Blues

BY THE TIME Will’s train was half way to London the following morning, his son Charlie was entering his supervisor’s room in a large concrete block. She had the typescript of the first two chapters of his thesis on the desk before her. It was an ethno-musicological study of the blues. The epigraph, visible on the top page of the pile of sheets before her, was from Andrew Marvell:

My love is of a birth as rare

As ’tis for object strange and high:

It was begotten by Despair

Upon impossibility.

It began, whackily but engagingly, and not a little troublingly for his supervisor Jennifer Halley, with a meditation on two paintings by Stanley Spencer. This was a trick he had learnt from his father. The paintings were Seated Nude of 1936 and Double Nude Portrait: The Artist and His Second Wife, 1937. What these paintings jointly showed, so Charlie argued anyway, was the impossibility of desire. Dear Hilda, Stanley’s first wife and the subject of his Seated Nude of 1936, gave herself to the artist, and was no longer desired, not enough anyway, neither for her purposes nor his, not with the passion he reserved for Patricia. Hilda as an object of desire had been translated from the realm of impossibility to that of melancholy, and it showed in her face, which had become a microcosm of the world’s griefs and disappointments.

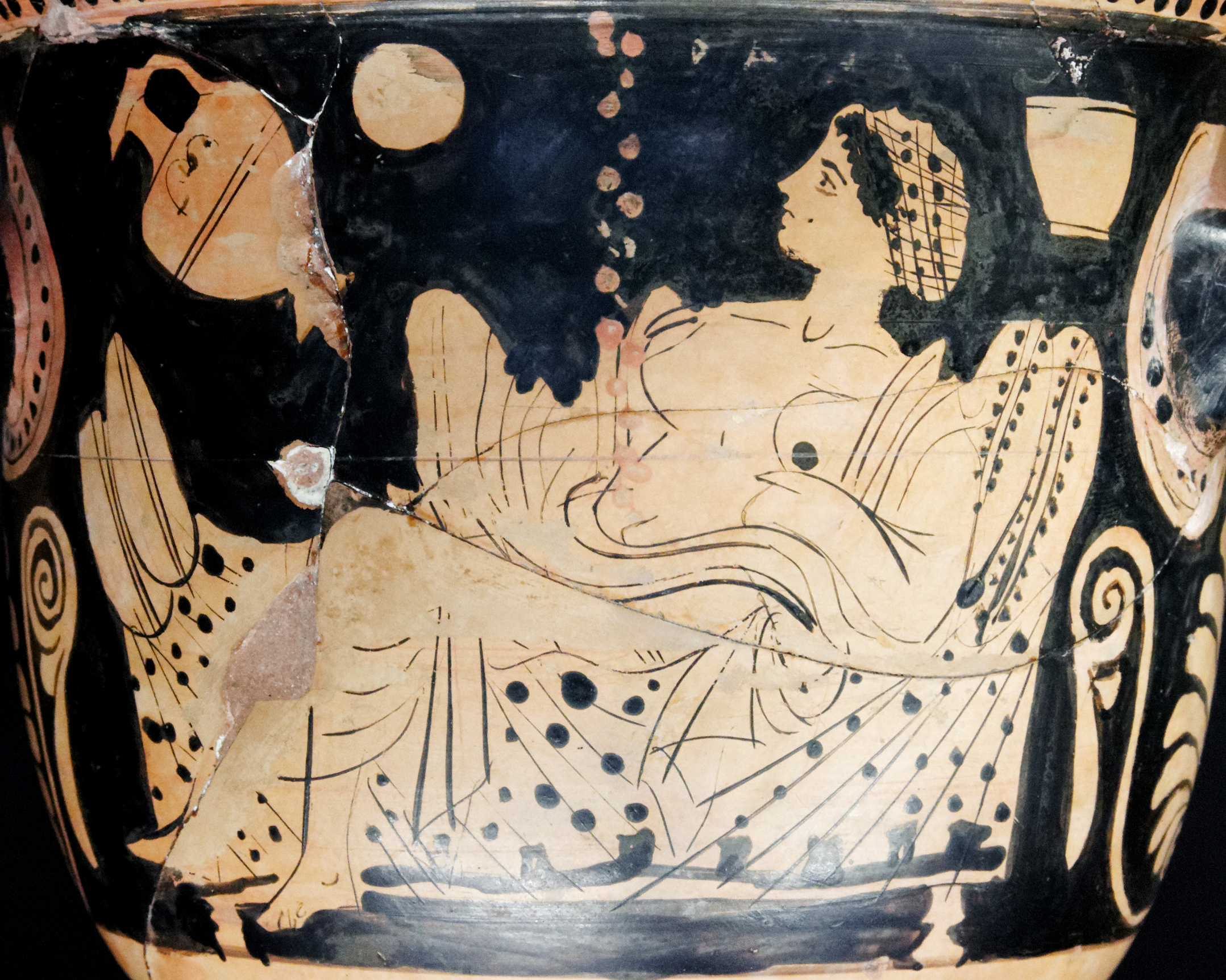

Here then was a midrash upon Zeus visiting Danaë in the fastness of her tower.

But Patricia Preece, grotesque, manipulative, deceitful, with no interest in the painter except for his worldly goods, and about to cheat Stanley out of his beloved family home in Cookham, Patricia was the true object of desire: impossible in every crease of her flesh. If desire had a dragon’s maw, Patricia was that all-consuming mouth. Stanley saw it; lived it; painted it. If breasts had noses, Patricia’s had turned hers up at him. He painted her eyes full of hunger, and they were too. Not for him though, only for his money. Here then was a midrash upon Zeus visiting Danaë in the fastness of her tower. This time the maiden would be impregnated by the gold, while leaving the god empty of everything except his craving.

Now the structure of the blues, so Charlie argued, functioned between the same two polarities shown in these portraits: impossibility and melancholy.

Now the structure of the blues, so Charlie argued, functioned between the same two polarities shown in these portraits: impossibility and melancholy. The first line of any blues song was never entirely repeated in the second, there was always an alteration, even an altercation, however slight, to give you the subliminal message that total reciprocity would be an abolition, a cancellation. In any case the third line of any blues song invariably pointed out to the two preceding ones that they had been facing, if only fractionally, in the wrong direction: While the first two lines spun on their (not entirely reciprocal) axis, the third came along to announce the annulment of all previous terminology and understanding in this case or any other.

His supervisor was relieved that he then moved into a discussion of Lévi-Strauss. The French anthropologist had studied primitive tribes, both exogamous and endogamous, and had concluded that kinship structures enacted a certain give-and-take between the tribe and exterior reality, particularly in regard to marriage transactions. The woman of one tribe became a donation to the other, a form of exchange with strict rules attached. But Charlie’s point about the blues was that it wasn’t the women who were interchangeable — since they could never ultimately be told what to do, though they could at times be locked away or shot, preferably with a .45, if only for the scansion of the lyrics — but their affections. Their affective faculties functioned as the exchange medium of joy and misery.

Woman I love I stole from my best friend

Yeah, the woman I love, stole from my best friend

Some joker got lucky, stole her back again.

There were only so many truths in the world: it was meaningless to assert copyright.

But if the affections of women were interchangeable, then so was the wisdom acquired by the blues singers and the songs themselves, derived as it was from all the sad shenanigans, the sordid misdemeanours, the sexual débacles. The lines above had been minted (though he had probably taken them from the air around him) by Blind Lemon Jefferson, passed on with some modifications to Skip James, and then been re-recorded, again with a shift in emphasis, by Robert Johnson. There were only so many truths in the world: it was meaningless to assert copyright. The elected restriction of the pentatonic scale that was common to all blues musicians allowed the universality of their themes to articulate themselves through one all-purpose form, without any unnecessary clutter: the impossible object, money; the impossible possession, love; the impossible state, happiness. Escape routes: railroads, riding the freight trains; another woman, briefly; drink; prison; death. Only the last entirely escaped the realm of the impossible, by terminating the realm of possibility itself with an unresolved hiatus, the way many of the songs ended on a seventh or an unresolved sub-dominant. With a breath no soul ever breathed.

Charlie reckoned she had been transposed to the melancholy realm quite early in life, whatever her impossible object of desire.

‘It’s a very oblique way to start a thesis, Charlie,’ Dr Halley said, sighing over the pages. She often sighed. Charlie reckoned she had been transposed to the melancholy realm quite early in life, whatever her impossible object of desire. They were sitting on the fifth floor of the social sciences building. When the musical department had moved away to another institution where it could be more adequately funded, ethno-musicology had remained. Since it carried implications of both sociology and anthropology, it had migrated to the social sciences block. This had not pleased Jennifer Halley much, who had never entirely worked out how she had ended up as a professor of ethno-musicology in the first place. Her original degree had been in music; her second in literature. An interest in the literary productions of that fecund figure, Anon, had led her inevitably to folk song. Her thesis had related folk song to the surrounding literature of seventeenth-century England. A musical literacy she herself had never thought much about had been remarked upon with wonder; and here she was now, dealing with the waifs and strays of the academic world, as they mused on sundry topics, from rap and urban anomie to the lyricism of Vaughan Williams. She had encouraged Charlie to maximise his use of Lévi-Strauss, as a propitiation to the anthropological gods surrounding them along the corridor. But she couldn’t help feeling that the use to which he put the great man was eccentric all the same, bordering indeed on the wayward. Charlie.

A musical literacy she herself had never thought much about had been remarked upon with wonder…

He stroked his hair as he spoke. Stroked his long black hair, that seemed to shine all the way down to his shoulders, stroked it with such unconscious affection, almost as though he were stroking her short ginger mop instead. Her hair. Cropped, scrubbed, forgotten wherever possible.

‘The blues is oblique. If it’s taught me one thing, Jennifer, it’s obliquity. That’s the name of the game. That’s why the last epigraph is from Emily Dickinson.’ Jennifer turned to the back page but there was no poem. ‘We haven’t got there yet. Tell all the truth, But tell it slant. Playing at Herders tonight, down at the end of Denmark Street. You should come.’

She looked at his guitar case on the floor behind him, then turned and stared out of the window, down on to the car park which it overlooked. How she hated this room. And ethno-fucking-musicology sometimes. What a way to make a living. She wanted a cigarette, which she was no longer permitted to have. Not in this room. Not in this building.

She looked at his guitar case on the floor behind him, then turned and stared out of the window, down on to the car park which it overlooked. How she hated this room. And ethno-fucking-musicology sometimes. What a way to make a living. She wanted a cigarette, which she was no longer permitted to have. Not in this room. Not in this building.

§

Chapter Four

Revels

AT SOME POINT green became concrete and brick, and the low murmur of the countryside re-tuned to the heartened thrum of the city. Will’s train arrived on time. He decided to walk from Euston. He wasn’t going to pay for a taxi and he hated the underground so much that he had vowed never to set foot on it again. Claustrophobia. Asphyxiation in the dark. Anyway, he felt like a walk. London. He had lived here for so many years. Been married here. Ditto divorced.

In his memory it was always teeming, a maggot-bowl of squirming humanity.

But where were all the people? Surely the capital was empty today. In his memory it was always teeming, a maggot-bowl of squirming humanity. Now here he was with these roads almost to himself. Was all memory mythic then? Somewhere towards Gordon Square he stood at a pedestrian crossing, waiting. A silvery blonde woman in a silver coupé braked to let him pass. He caught her eye. She smiled. Nothing but money could purchase a smile as expensive as that. Something silver on her lips was glittering too, some fresh stardust. A fresh-minted woman. She let him pass before pressing her foot back on the accelerator.

When he reached the National Gallery ten minutes later he walked in and went straight to Room 23. Rembrandt. He had no interest in the huge portrait of a man on a horse, the Rembrandt of public commissions and public faces. But the self-portraits, as always, held him utterly. In that steadfast gaze the artist held himself, and the gaze grew deeper and deeper the further he penetrated. In the course of a lifetime an ordinary Dutch self had deepened into a subjectivity so exemplary and problematic that it still held us all now as securely as it once held him. He shifted to his left and stared at the little picture of Hendrickje. The shadow between her breasts, what was that exactly? The shadow of the artist’s desire, the shadow of death, or the shadow of recognition that the two must merge, and were already merging? Death held every one of these portraits in its inescapable penumbra.

When he reached the National Gallery ten minutes later he walked in and went straight to Room 23. Rembrandt. He had no interest in the huge portrait of a man on a horse, the Rembrandt of public commissions and public faces. But the self-portraits, as always, held him utterly. In that steadfast gaze the artist held himself, and the gaze grew deeper and deeper the further he penetrated. In the course of a lifetime an ordinary Dutch self had deepened into a subjectivity so exemplary and problematic that it still held us all now as securely as it once held him. He shifted to his left and stared at the little picture of Hendrickje. The shadow between her breasts, what was that exactly? The shadow of the artist’s desire, the shadow of death, or the shadow of recognition that the two must merge, and were already merging? Death held every one of these portraits in its inescapable penumbra.

Up one of those streets that sprout north and south from the Strand, stood Revels, an underground wine bar favoured by Charlie and his musician friends. It was sepulchral, vaulted, slightly foisty and very dark. Candles which had melted into shapes of gothic extravagance, each a miniature Gaudi of white wax, stood on upturned barrels serving as tables. The waiters and waitresses were pleasantly disrespectful. The house wine was drinkable and cheap. Even the food wasn’t too bad, and there was always somewhere to sit. Once upon a time it had been the wine cellar for a mighty house no one could now remember the name of.

Charlie felt weary, though he didn’t look it.

Charlie was already sitting at one of the barrels when Will arrived. He had been going through Jennifer’s marginalia on his thesis. Some drift beginning here, Charlie. Beware of simply asserting your own opinions as though they are fact. You need to give more background on Blind Lemon Jefferson. To what extent was the blues derived from African roots? I wonder sometimes if you slide too easily into philosophizing. Charlie felt weary, though he didn’t look it. His father made out his shape in the shadows. Charlie stood up and they embraced briefly.

‘You look good,’ his father said. It is a curious thing for a man to see his own child entirely adult. A mixture of achievement and loss can confuse the emotions. ‘Studying the blues must be keeping you cheerful, Charlie.’

‘Not sure about that. Playing them might. What do you want to drink?’

‘I’ll have one glass of wine and make it last. Lecturing tonight.’

‘No problems with your medication?’

‘No, that’s all settled down now.’

‘Omelette?’

‘Omelette’s fine. Whichever one they do with no meat.’

‘That one’s just called an omelette.’

‘Is there anything inside it though?’

‘Omelette’s inside it.’

He could still remember that blob of screaming flesh in the night, eyes bewildered and bleared in the midst of it.

He was touched by such solicitude about his medication. As Charlie walked over to the bar Will picked up the typescript of his son’s thesis and started flipping through it. Then he turned and looked at the tall, sleek creature buying him a drink and ordering the food. He had held him in his arms when he was only a foot long, dabbed his tears away, towelled off his acrid smearings, comforted and cuddled the little shrieking bundle. He could still remember that blob of screaming flesh in the night, eyes bewildered and bleared in the midst of it. And now look. Just look. As tall as Will, black hair beautiful as a woman’s, the same high cheek bones and blue eyes of his father, but without any of the damage life had undoubtedly brought to his old man. No wrinkles, creases, bruises under eyes. He dressed well too, in his blue Levis and brown leather jacket. His moccasins made him look entirely at home in the world. As though he could relax upon its curved surface anywhere he chose. An Indian at home on the plains.

He was touched by such solicitude about his medication. As Charlie walked over to the bar Will picked up the typescript of his son’s thesis and started flipping through it. Then he turned and looked at the tall, sleek creature buying him a drink and ordering the food. He had held him in his arms when he was only a foot long, dabbed his tears away, towelled off his acrid smearings, comforted and cuddled the little shrieking bundle. He could still remember that blob of screaming flesh in the night, eyes bewildered and bleared in the midst of it. And now look. Just look. As tall as Will, black hair beautiful as a woman’s, the same high cheek bones and blue eyes of his father, but without any of the damage life had undoubtedly brought to his old man. No wrinkles, creases, bruises under eyes. He dressed well too, in his blue Levis and brown leather jacket. His moccasins made him look entirely at home in the world. As though he could relax upon its curved surface anywhere he chose. An Indian at home on the plains.

‘You start with paintings,’ Will said when Charlie came back.

‘A chip off the old block, eh? Always start with something far away from your subject, then you’ll find the whole subject flows in and out of that distant spot. I think I quote you verbatim. I’m accused of philosophizing too much as well.’

‘Tell them it’s a hereditary taint. I’ll give you a note to take in if you like.’

‘Like the ones you used to give me for games.’

‘My son’s philosophizing is a medical condition which has been proved to be involuntary.’ They both smiled. It always seemed to surprise them how much they liked one another whenever they met. One of the waiters brought their omelettes over. Nothing in Will’s omelette but more omelette, though Charlie’s was flecked with ham.

‘Do you have a thesis yet, Charlie, or is writing the thesis the way to find out what it is?’ His son chewed thoughtfully before speaking.

‘I reckon some of the best people I study were actually made out of songs — they became them.’

‘I think I believe in the songs, dad. The more I study it all the more I believe in the songs. They’re better than any thesis. Poetry in three-minute snatches. You carry them around inside you. They become you. I reckon some of the best people I study were actually made out of songs — they became them.’

Will had a sudden memory, a vision heartbreaking in its momentary intensity, of Charlie at twelve trying to form some chord too big for his fingers, but refusing to stop. Sitting by the window in the old house. Almost crying finally, at the resistance of the steel strings. One of his fingers had ended up striated. That had been the year of the separation.

‘What’s philosophy for, dad? You’ve been at it most of your life. Have you worked it out yet?’ Will paused. His thoughts at the moment were dark, as his lecture that evening would show.

‘Well, if the philosopher has a function at all at the moment, and I do sometimes wonder, it’s to discover the dark side of things — to stop pretending that the night is merely for sleeping in.’

‘Been down so long it feels like up to me.’ Charlie picked up his typescript and turned the pages till he found a quote. It was from Alan Lomax, talking about how much of the blues came from chain-gangs. How blues music had been squeezed out from the soul’s oppression and, like crushed grapes, once it had been left to ferment long enough, it became potently intoxicating.

‘It doesn’t have to be an either/or, does it Charlie? Can’t we have philosophy and the blues as well?’

Sing it and you are it. In the end you’re honeycombed with your own music.

In the gloom of the cellar Charlie began to speak with evident affection about the songs that meant the most to him. The heroism of the songsmiths and the singers. To hold so much in your heart and memory and deliver it with such aplomb. To be so full of insouciant grace in the face of such adversity. How the difference between a singer and an actor is that the singer must somehow learn to mean it, not just appear to. Sing it and you are it. In the end you’re honeycombed with your own music.

‘These are our memory men, that’s why we love them. They keep taking us back, however strong the forward tug. What did you used to call such people?’

‘The Tribe of Mnemnosyne.’

‘Evangelists in the darkness. I just sometimes wonder, if the house of truth really is coming crashing down about our heads, then why bother philosophizing at all?’

‘Maybe we can’t help ourselves. What else are we supposed to do?’

‘Sing. Learn the song and sing it. Why theorize, why quibble, why spout? Sing your song while you still have breath, then get on with dying when you don’t. There’s songs for that too, plenty of them, believe me. See that my grave is kept clean.’ Charlie had effortlessly quoted from blues songs for as long as Will could remember.

‘Can the song really be the whole of life, Charlie? Can you fit everything into it?’

‘I sometimes think music is the same as morality’.

‘I sometimes think music is the same as morality. If you can play it properly and sing it properly, then that’s maybe as good as you’ll get. Technique: in music as in life it’s the only real test of seriousness.’ The little boy with his striated finger and the tears almost filling his eyes. Then they both fell silent. Without thinking about it, Charlie patted the guitar case he had carried in. A lot of money there, Will thought. The whole of his son’s inheritance from the family fund when he was twenty-one. It had astounded everyone, everyone except the oldest of the old men, Will’s father, Charlie’s grandfather, who had smiled in characteristic perversity, and quietly applauded. Forty thousand pounds for one guitar. A Martin from the 1930s. Finally Will asked, ‘How’s mum?’

‘I sometimes think music is the same as morality. If you can play it properly and sing it properly, then that’s maybe as good as you’ll get. Technique: in music as in life it’s the only real test of seriousness.’ The little boy with his striated finger and the tears almost filling his eyes. Then they both fell silent. Without thinking about it, Charlie patted the guitar case he had carried in. A lot of money there, Will thought. The whole of his son’s inheritance from the family fund when he was twenty-one. It had astounded everyone, everyone except the oldest of the old men, Will’s father, Charlie’s grandfather, who had smiled in characteristic perversity, and quietly applauded. Forty thousand pounds for one guitar. A Martin from the 1930s. Finally Will asked, ‘How’s mum?’

‘Fine. Are you seeing her tonight?’ Will shook his head.

‘I sent her an invitation to the lecture.’

‘What’s it on?’

‘Wittgenstein and Naming.’ Charlie started laughing.

‘Might have caught her the one night she’s washing her hair then.’

‘She said she had some publishing function to attend.’

‘Oh, that’s right, I’d forgotten. Something to do with Maddox.’

‘She hates Maddox.’

‘Mum hates quite a lot of people. She says it’s inevitable if you work in publishing but she can be remarkably nice to them face to face, all the same. I suppose that’s inevitable too, if you work in publishing. Mum sees herself reflected in men’s faces, dad: you know that.’

‘I sometimes think the world is made of mirrors for your mother.’

Whenever she looked in a mirror she was the entirety of the mirror’s world, which was exactly the way it should be, according to her way of thinking.

This wasn’t fair. Charlie’s mother was fond of mirrors, it was true — the sun visor in the car with its vanity reflector on the reverse would be pulled down every time she stopped at a traffic light — but she knew mirrors didn’t constitute the world. The world, as the first words of the Tractatus tell us, is everything that is the case. For there to be an image in a mirror, it had to be an image of something beyond the mirror’s surface. And Marie was more than happy to be that something. Whenever she looked in a mirror she was the entirety of the mirror’s world, which was exactly the way it should be, according to her way of thinking. Will was shaking his head.

‘But Maddox…’

When not gerrymandering his review pages to fit his prejudices and proclivities, he sententiously sounded off in his own column as to the status of the book in the modern world…

Maddox was a literary editor so corrupt that the father of his godchild knew he could never receive a bad review in his newspaper; however flat, banal or trite the book, it would ineluctably elicit a honeyed notice and any negativity, however timorous, would be spiked. When not gerrymandering his review pages to fit his prejudices and proclivities, he sententiously sounded off in his own column as to the status of the book in the modern world, the interaction of printed word with lived reality, the meaning of literary heroism. Universally loathed by his staff for the petulance and imperiousness with which he conducted himself from morning till night, he was nevertheless much-courted by authors and publishers. He had refused to review Will’s one book, Kicking Away the Ladder, on the grounds that it was too specialised.

‘So life, death, the universe, etc. are all too specialised for him are they?’ Will had asked. He’d hated the man on principle ever since.

‘I believe he’s written his literary memoirs, dad. All those famous writers he’s hobnobbed with over the years. And he kept all the photographs.’

‘Yes, I bet he did. Your mother can still disappoint me sometimes.’

‘She says you live in an ivory tower. Says that it’s only the likes of her toiling with the sweat of her brow that keeps the likes of you and me inside our libraries.’

‘Ivory Tower? Made out of what’s left of Fanshawe Ivory, I suppose. The last time I looked, mine was made of corrugated tin.’ He thought of Mercia College. He thought of Beth. Ah, yes — Beth.

‘Charlie, you did tell me you could do CD-ROMs didn’t you?’

‘No dad, I told you I could do CDs. On my computer I’ve got Cubase and a burner. I can record my own music and burn discs one at a time. CD-ROMs are another kettle of fish entirely. You’d need different software for that. And I don’t have it. In fact, I’m not sure anybody does CD-ROMS any more.’

‘Mother and son are both starting to disappoint me today. Well I’d better go and check in at the hotel, I suppose. When you see mum next, give her my love. Tell her I hope she gets offered the Maddox book. Piccies and all. Maybe she’s even in one, reflected in a mirror. You are coming up for grandad’s birthday?’

‘I’ve booked the Shepherd’s Cottage for a week.’

♦

—This is the second installation of White Ivory. —

See previously

chapters 1 & 2

ALAN WALL was born in Bradford, studied English at Oxford, and lives in North Wales. He has published six novels and three collections of poetry, including Doctor Placebo. Jacob, a book written in verse and prose, was shortlisted for the Hawthornden Prize. His work has been translated into ten languages. He has published essays and reviews in many different periodicals including the Guardian, Spectator, The Times, Jewish Quarterly, Leonardo, PN Review, London Magazine, The Reader and Agenda. He was Royal Literary Fund Fellow in Writing at Warwick University and Liverpool John Moores and is currently Professor of Writing and Literature at the University of Chester and a contributing editor of The Fortnightly Review. His book Endtimes was published by Shearsman in 2013, and Badmouth, a novel, was published by Harbour Books in 2014. A collection of his essays was issued by Odd Volumes, The Fortnightly Review’s publishing imprint, also in 2014. A second collection, of his Fortnightly reflections on Walter Benjamin, followed in 2018, and a third collection, Midnight of the Sublime, has just been published. An archive of Alan Wall’s Fortnightly work is here.

ALAN WALL was born in Bradford, studied English at Oxford, and lives in North Wales. He has published six novels and three collections of poetry, including Doctor Placebo. Jacob, a book written in verse and prose, was shortlisted for the Hawthornden Prize. His work has been translated into ten languages. He has published essays and reviews in many different periodicals including the Guardian, Spectator, The Times, Jewish Quarterly, Leonardo, PN Review, London Magazine, The Reader and Agenda. He was Royal Literary Fund Fellow in Writing at Warwick University and Liverpool John Moores and is currently Professor of Writing and Literature at the University of Chester and a contributing editor of The Fortnightly Review. His book Endtimes was published by Shearsman in 2013, and Badmouth, a novel, was published by Harbour Books in 2014. A collection of his essays was issued by Odd Volumes, The Fortnightly Review’s publishing imprint, also in 2014. A second collection, of his Fortnightly reflections on Walter Benjamin, followed in 2018, and a third collection, Midnight of the Sublime, has just been published. An archive of Alan Wall’s Fortnightly work is here.

Image credits: Guitar, PLotulitStocker; Rembrandt, self-portrait,1632; Danaë, Wikipedia; woman in mirror, Choirul Anwar;