< chapters 7 & 8 chapters 11 & 12 >

A Fortnightly Serial.

By ALAN WALL.

•

Chapter Nine.

Over the Rainbow

WILL HADN’T BEEN able to get away on the Friday. He’d had to go in for some tutorial sessions. Finally he had made his exit. As he walked along the corridor he saw the unmistakable figure of Ken Malmsey, wearing his trademark calf-length black Barber coat. It flapped behind him as he walked; crow-strut on a grave.

WILL HADN’T BEEN able to get away on the Friday. He’d had to go in for some tutorial sessions. Finally he had made his exit. As he walked along the corridor he saw the unmistakable figure of Ken Malmsey, wearing his trademark calf-length black Barber coat. It flapped behind him as he walked; crow-strut on a grave.

It had all been held together by one allusive image: that piers and towers were both disappointed bridges,…

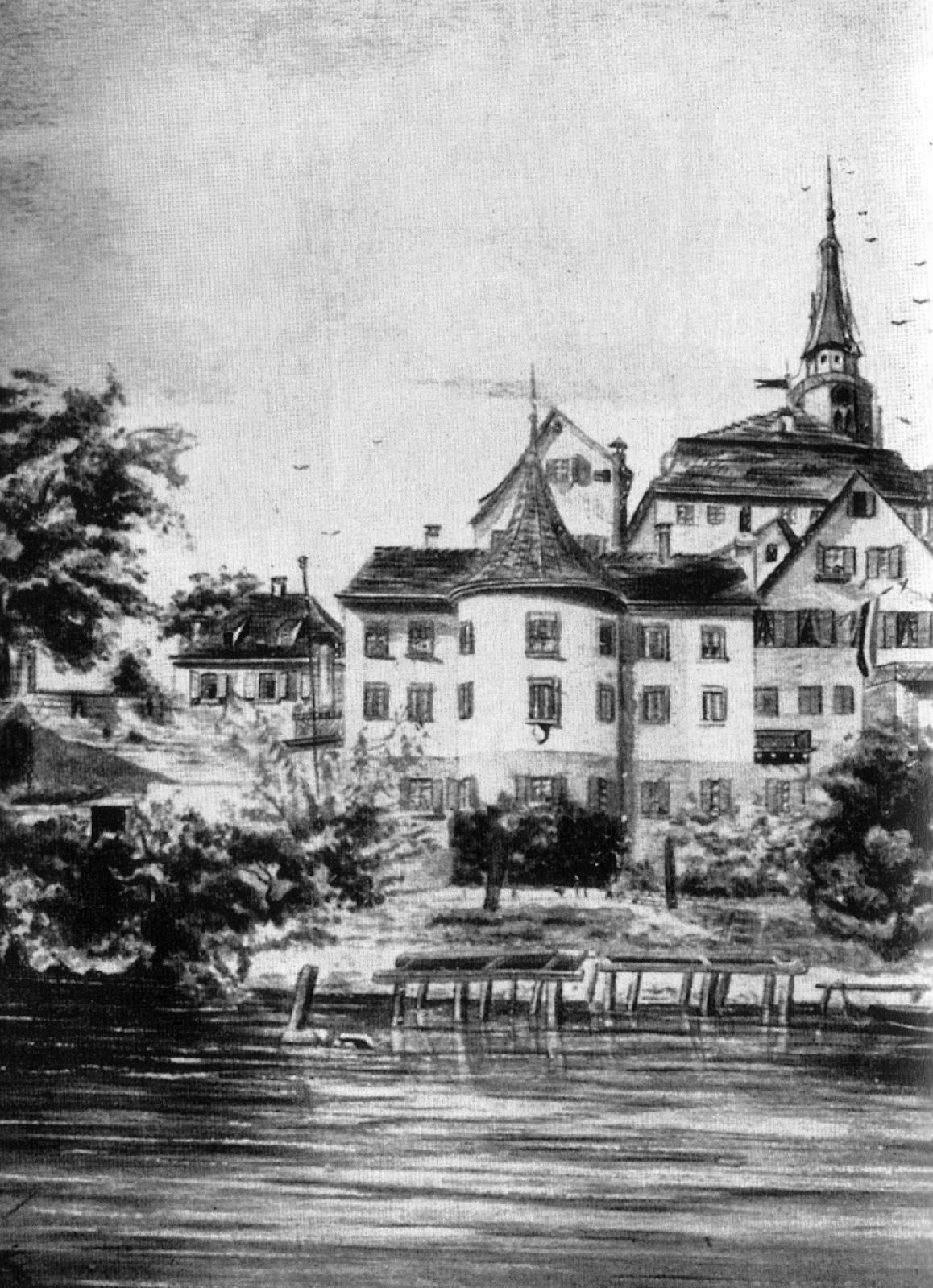

Ken had made a name for himself on the basis of one book, Hölderlin on the Pier. This was a slim volume so slim it risked anorexia. But it had been cunningly devised. Ken had taken Hölderlin’s classic imagery and had combined it with data from his self-incarceration in the tower at Tübingen, then these had all been shaped into the pier of a northern seaside resort, with images from Hancock’s Punch and Judy Man, plus crystal balls and ancient slot machines which still swallowed ancient pennies made of copper alloy. Coins weighty with history, showing the eroded features of Queen Victoria or King Edward. Metal talismans that warmed in your palm.

What was cunning about it, Will had come to realise after some years of pondering the matter, was that all the energy of the book, all the compelling figures and devices, came from Hölderlin. Ken had simply re-employed them. It had all been held together by one allusive image: that piers and towers were both disappointed bridges, one to the stars and the other to the farther shore. Any poems he had subsequently written in his own imagery, about his own life, his own emotions, had been trite and passed over largely without remark. But on the basis of this one book and a couple of anthologies of writing co-edited with others, he had now ended up in charge of the Writing Programme. And he liked that very much indeed. He liked it because it made him a minor Renaissance prince with beggars queueing at his door. These were the graduates, seeking to discover if Ken’s goodwill might solve their lives for them over the next year. Throw me a few classes from your high window and your mighty name will echo through the streets, through the campus, my lord. He wielded power and knew it. Hölderlin would surely have hated him. There was also a curiosity that Will often remarked to himself: Ken’s substantial reputation was based on his ability to turn people into successful writers. He himself was not a successful writer; never had been; never would be. No one he had ever taught had gone on to become a successful writer. In fact most of them were still queueing outside his door. Yet this foundational flaw had in no way restricted the ever-accruing edifice of his academic career.

‘Time for a coffee, Will?’ Will hesitated and Ken took him by the arm and steered him back along the corridor where he had just been. The Head of the Writing Programme prided himself on his forcefulness of character. ‘Come on, we haven’t spoken for ages.’

‘As long as you don’t tell me you’re on sabbatical again when I ask what you’re doing.’

‘I won’t.’

‘Promise.’

‘I promise.’

‘So what are you doing then?’

‘I’m on sabbatical actually.’

Most writers of any worth who came into his programme soon cleared off in search of an environs less oppressive with corporate sponsorship and unreality.

Ken had so many sabbaticals that Will couldn’t see how he could manage to fit a new one in between all the others. Will wondered why he didn’t simplify his arrangement with the university to a post-restante address in the Mediterranean where they could send the cheques to him each month, while he researched the effects of sunlight on waves and sand. Most writers of any worth who came into his programme soon cleared off in search of an environs less oppressive with corporate sponsorship and unreality. Ken came by from time to time to monitor the length of the queues outside his door, or to gaze with evident glee at the pleas and petitions crammed into his pigeon-hole, but the courses he was technically in charge of these days were usually supervised by Lola Charmont. Will had taught a joint session with her once, something about the philosophy of writing. Her teaching style exhibited all the vigour of an anaesthetized sloth. She had spent her first five minutes talking about who she was; her unfinished thesis; how she too was only a student, lumbering endlessly on towards an ever-unachieved qualification. By the end even the air was yawning. Will, who always adopted a sprightly mode of attack in his teaching, who famously went to it with vigour and vim, had been appalled. He couldn’t work out how she got away with it. But the money kept pouring in and the students came by the boatload to be instructed how to become successful authors. They never seemed to notice that this did not happen.

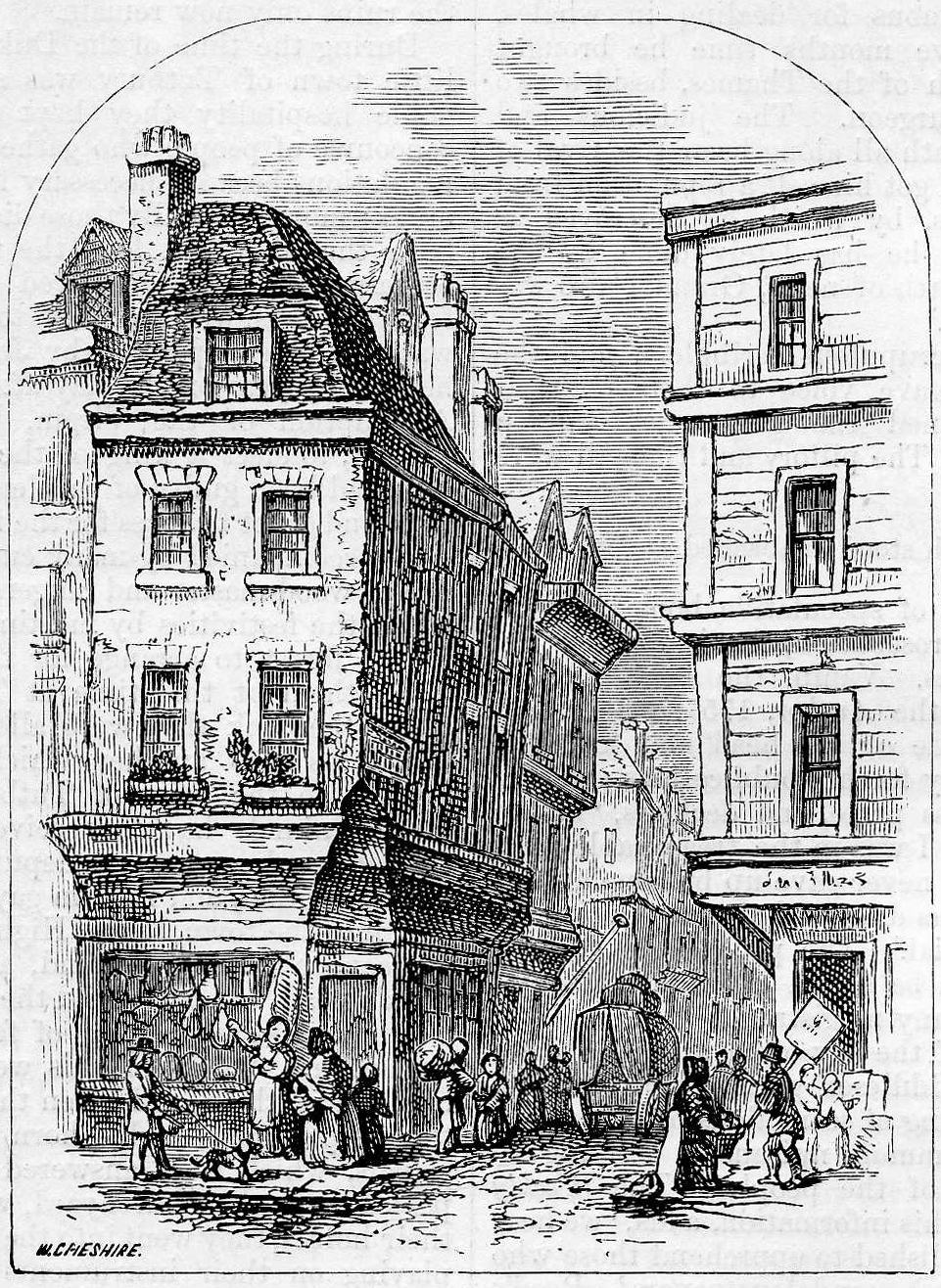

They passed the final room of the corridor. Will peered in briefly through the open door. Paul Phillimore was there as usual, shambling and shuffling about inside the vastness of his hair and beard, variegated grey and white, all six foot six of him. Sometimes as Will walked past that lair he wondered if he shouldn’t throw in a jar of honey. Paul had not the slightest notion what was happening around him, despite the word ‘Professor’ engraved on his door. Though he could give you a detailed topographic account of Grub Street circa 1760.

They passed the final room of the corridor. Will peered in briefly through the open door. Paul Phillimore was there as usual, shambling and shuffling about inside the vastness of his hair and beard, variegated grey and white, all six foot six of him. Sometimes as Will walked past that lair he wondered if he shouldn’t throw in a jar of honey. Paul had not the slightest notion what was happening around him, despite the word ‘Professor’ engraved on his door. Though he could give you a detailed topographic account of Grub Street circa 1760.

As they arrived at the counter, Ken said brightly, ‘At least I don’t have as many sabbaticals as Joseanne.’ This was true. Her sabbatical existence had become legendary. It was rumoured her first had been taken pre-natally. An early book on language had brought her unfathomable fame and fortune, and she had been making the best of it ever since. She lived around universities and in them, but had nothing whatsoever to do with the students, unless she noticed one who particularly took her fancy. It was rumoured that her newspaper columns alone brought her over eighty thousand a year.

‘And where’s Jo at the moment?’

‘Egypt.’

‘Buying herself a pyramid, is she?’

‘Knowing Jo, she’s probably arranging to sell one.’

At this point Ken’s ten-year-old son arrived.

He couldn’t help wondering if Ken might be employing his own son as a prophylactic against oncoming critiques.

‘Hello Billy,’ Will said and smiled. He liked the boy well enough and remembered briefly what Charlie had been like at that age. But there was something about the way Ken brandished this boy about the place, placing his small fist in the hands of the grown-ups, that made him suspicious. He couldn’t help wondering if Ken might be employing his own son as a prophylactic against oncoming critiques. As one who might say, ‘Don’t accuse me of being self-important and imperious. Don’t say I run all this in a manner that simply serves my needs. I’m a new man. I take my little boy with me everywhere. I don’t expect my womenfolk to do all the minding. Those days are gone, my friend.’

‘Shake hands with Will,’ Ken said, carefully placing the little boy’s hand in Will’s. They shook, and kept shaking, and Will kept his smile fixed, weary though it grew. Then he suddenly turned to catch Ken’s eye, his big brown eye. Ken seemed to have momentarily lost his perch on the axis mundi. And behind all the assertiveness training, the trail of beggarmen and scribblers leading to his door, Will caught something in the face of the Head of the Writing Programme which he thought he had seen there before: an insecurity so vast it rolled like the ocean. Who are you Ken, he thought, do you really have even the slightest notion who you are?

•

AT NEW STREET the Chester train was, as so often, cancelled. Will made for the bar, the noisy, smoky bar, and asked if they had any drinkable wine. They did. Something Australian and chilled. He ordered a large glass of it and went over to the corner to sit down. A large black woman was sitting alone in front of an empty glass.

AT NEW STREET the Chester train was, as so often, cancelled. Will made for the bar, the noisy, smoky bar, and asked if they had any drinkable wine. They did. Something Australian and chilled. He ordered a large glass of it and went over to the corner to sit down. A large black woman was sitting alone in front of an empty glass.

‘Anybody sitting here.’

‘No love.’

When that was cancelled too, he wondered if he should get angry.

He pulled out his book. He drank and he read until the next train to Shrewsbury half an hour later. When that was cancelled too, he wondered if he should get angry. He reminded himself of the terms of his medication and went back to the bar instead. He ordered the same again. And then went over to the same table. She was still sitting alone there in front of an empty glass, looking utterly serene. Once more he started reading. Only ten minutes before his train was due in did he finally put the book down and look into her face. She started smiling.

‘My name’s Dorothy. I sit here at this time in the evening because that’s how I make my money, in case you were wondering. There’s usually a businessman of some kind who needs a little bit of something he doesn’t get at home. It’s how I make my living, you see, how I feed my kids. I’m very kindly. Not all the girls are, these days. With some of the stuff they’re on, they haven’t really got time for anybody else’s problems, which is what this game’s all about really. I’m a great listener, you see, but I can listen with my hands as well. I do a full massage. Do you ever get lonely at home sometimes? What’s your name, love?’

‘Will.’

‘Do you ever get lonely at home, Will?’

‘Yes.’

‘I don’t live far from here…’

‘How much do you need a night, Dorothy? To feed your kids.’

‘Forty quid gets me clear. Otherwise I’m fucked. ’Scuse my French, Will.’

No sooner did Will consider it than he did it: he took the money from his pocket. He had been to the bank on campus that morning. He gave her two twenty pound notes. She smiled at him.

‘It’s only ten minutes in a taxi. As long as you don’t mind paying for the taxi.’

Dorothy looked hard at him, a look both quizzical and affectionate. The twenty-pound notes were still in her hand.

‘It’s all right, Dorothy. Go feed your kids. God loves you.’ Will leaned over and kissed her on her mighty forehead. She smiled an even mightier smile. He put the book in his bag and stood up. There were tears in his eyes. Dorothy looked hard at him, a look both quizzical and affectionate. The twenty-pound notes were still in her hand.

‘Do you actually believe in God, Will?’

‘I don’t know. But I believe in His love anyway. I believe in everybody’s love. Does that make any kind of sense?’

Dorothy looked at him, still smiling, evidently nonplussed.

‘Not to me it doesn’t, no.’

‘I believe in the predicate even if its subject might have left us for another creation. Any idea what I’m talking about, Dorothy?’

‘Not the faintest, Will. But thanks for this, all the same. You’re a good man.’

‘Because I gave you money?’

‘No. Something in your face.’

Will started to go for his train. He got to the glass door before he turned back.

‘Dorothy,’ he said with some urgency, ‘do you ever sing the blues?’

‘Sometimes. In a way, I suppose I do, yes.’ She started laughing. ‘Not going to ask me to sing now, are you?’

‘Do you ever pray?’

‘Every night.’

Pray for Charlie, the blues singer. Promise?’

‘Then pray for my son. He sings the blues. Pray for Charlie, the blues singer. Promise?’

‘You’ve got forty quids worth of praying coming up. You’re a strange one, Will, but I do like you. Sure you won’t come back?’

‘I’m sure. But don’t forget those prayers now, whatever else you do.’

§

Chapter Ten.

The Mount

BY THE TIME Will got back to Oswestry he couldn’t face going over to the Mount. It was only four miles, but he was tired. He would see everyone the next day. He phoned and explained.

And the next morning when he arrived he was met at the door by Lindsey.

‘Just in the nick of time, Will. The off-license called to say they can’t deliver our drinks, after all. Van driver’s wife is having a baby. Could you go with Frank and pick the stuff up? It’s all been payed for.’

The two brothers drove down in Frank’s new silver Range Rover. After they had loaded the cardboard boxes filled with booze into the back, they were waiting for the traffic lights to change colour. Will was staring through the window thinking of Dorothy.

For the second time in twenty-four hours Will felt his eyes start to fill with tears.

The young woman was seriously misshapen, her bottom a vast, twin dirigible in her blue tracksuit trousers, with the oatmeal labrador beside her in its metal frame with the white leather attachments. Blind then, or not far off. And in her lumbering sightlessness, the dog devotedly wagging beside her, she was accompanied by a young man. He was trim and far from unattractive. He shielded and steered her out of harm’s way, and his arm around her sagging and defeated shoulders somehow bespoke a nobility of spirit over the wet cobbles that morning. For the second time in twenty-four hours Will felt his eyes start to fill with tears. He remembered Nietzsche’s denunciation of pity at the beginning of Genealogy of Morals. He understood it but knew that its truth wasn’t large enough to hold what life demanded. ‘Look,’ he said softly to Frank, hardly able to get the words out of his drying mouth.

‘Look,’ he said softly to Frank, hardly able to get the words out of his drying mouth.

‘I know,’ Frank said. But then Frank always knew. He put the car into gear and accelerated. ‘Disgusting isn’t it? Just look at the fat cow. Imagine fucking that. He’s the one who should be blind, not her. You’d think he might do a bit better for himself. Quite a nice-looking boy, actually.’

Will turned to look at his elder brother, who was smiling his all-purpose smile of self-congratulation. Something wet and icy around Will’s heart felt the chill. He realised with sudden clarity how much he hated his brother, and he turned away from him to catch a last glimpse of the damaged couple.

…he prattled in paint as merrily as he prattled in words.

That evening they all sat around the long table. Behind them on the walls were some of Frank’s paintings. When not estate-managing or fund-financing or end-of-year accounting, Frank liked to paint. He had even had a little exhibition at a Shropshire gallery, though there was a suspicion that he had financed it himself. Will looked at a picture of a half-articulated vegetable shape on a salmon ground, entitled ‘Photosynthesis’, and it struck him that it was the visual equivalent of Frank’s talk: he prattled in paint as merrily as he prattled in words. He was prattling now at Will’s son.

‘Oh come on, Charlie, you’re not trying to tell me that blues songs have any wisdom in them. What wisdom’s that then? That women are unfaithful and black men spend a lot of time in jail? I don’t need to listen to some tuneless old man droning on for hours to work that one out, thank you very much. I prefer opera.’

‘I don’t think you’ve ever listened to these songs properly,’ Charlie said mildly. I shouldn’t think he’s ever listened to anything properly in his life, Will thought to himself.

‘So what does my brother say? What does young Will have to say?’

‘A hundred billion neurons in your head. That’s more neurons inside that skull of yours than there are stars in the universe, Frank. To count the synapses you’d have to add quite a few more zeroes. You still have some space left. Don’t close the whole area down prematurely.’

‘I think you take my point, Will, all the same.’

‘I think you should take your own point and put it where it belongs, Frank, amongst all the other blunted needles in your mind.’

‘Ah, now here comes my brother the philosopher with his kit-bag of precisions.’

At which point the old man himself intervened. He was seated at the head of the table, in his specially braced chair; it was after all his birthday party.

‘I take it you’ve all met my sons. We would have called them Cain and Abel but there was some sort of copyright problem. As it happens, Frank, I’m very fond of Charlie’s music. I’ve asked him to bring his guitar here tonight to play me some. And if you don’t like it, you can go and do the washing-up instead. After all, we don’t have servants any more. You said we couldn’t afford them.’

Her white hair was cropped, and she hardly ever spoke a word. She simply sat and endured her husband.

Sitting next to Frank as always was his tiny wife Colette. Her white hair was cropped, and she hardly ever spoke a word. She simply sat and endured her husband. Poor Colette. Her white hair and her husband’s black curly mop beside her. Surely he dyed it. .Will found himself looking at her from time to time as he made his next little speech. She remained expressionless. It was impossible to fathom what she really thought. There had been some speculation, given their childlessness, that theirs was a mariage blanc; that Frank’s interests in fact lay elsewhere. You wouldn’t discover anything about it by looking at Colette’s face, that was for sure.

‘Wittgenstein knew a man called Ramsey. Ramsey was no fool. Ended up as Professor of Philosophy at Sydney. So, plenty of intelligence then. To use one of Wittgenstein’s favourite phrases, enough intelligence to feed the pigs. They’d known each other for some considerable time. One night they had a furious argument, an argument that led to them not speaking or writing for years. Somebody asked Wittgenstein much later what could conceivably have been so important as to lead to such a sundering quarrel.

‘Wittgenstein knew a man called Ramsey. Ramsey was no fool. Ended up as Professor of Philosophy at Sydney. So, plenty of intelligence then. To use one of Wittgenstein’s favourite phrases, enough intelligence to feed the pigs. They’d known each other for some considerable time. One night they had a furious argument, an argument that led to them not speaking or writing for years. Somebody asked Wittgenstein much later what could conceivably have been so important as to lead to such a sundering quarrel.

‘Do you know what Wittgenstein said?’

‘You’re obviously going to tell us, Will, so you might as well get on with it and stop being coy.’

‘He said there was something about Ramsey’s inability to be surprised by life; about his assumption that he knew the answer to every question before the question had even been fully formulated; about his sheer lack of reverence, his endless knowingness in the face of all creation — something about all this that repelled and disgusted him, and he could no longer hide the disgust he felt. So he expressed it — forcibly, having no alternative.’

‘And I’m Ramsey, am I Will?’

‘You’ll have to try to work the story out for yourself, though he was called Frank as well, funnily enough.’ Everybody left the room to go next door where Charlie was tuning up his guitar. Only Will and Frank remained at opposite ends of the table staring silently at one another. Finally Frank spoke.

‘Not easy to live with, Wittgenstein, by the sound of it. I believe the blues are getting started in the other room, Will. Your little boy is singing for his supper.’

Will needed to be alone, if only for five minutes. He walked up the staircase until he was outside the big bathroom. He pushed the door gently until it swung into the darkness. Soft smell of soap and salts.

The first time Will had ever taken Marie back to the Mount, she had only returned two days before from a month in Italy. It was August and her skin had darkened beautifully beneath the Tuscan sun. Her black hair, and her red bandanna gave her a distinctly exotic appearance. Will’s father had taken one look at her and said, ‘You are not from these shores, I think?’

The old man had never subsequently relinquished the notion of her foreign blood, her foreign nature.

‘Sì,’ she had replied, employing pretty much her entire Italian vocabulary in that single moment. And that was it. The old man had never subsequently relinquished the notion of her foreign blood, her foreign nature. Nothing would shake this colossal misconception. The patriarch had disapproved of the marriage. The day before the ceremony, ten minutes before he went out for his stag night, Will had sat in this very bathroom where his father was, as so often, lying in state in his porcelain bath, easing the pains in his back. Will had hoped for a final blessing, like Jacob approaching the blind Isaac. There was only one day to go. But his father was having none of it.

‘Do you have any conception of the size she’ll be after a few years of marriage? Ever blown up a pink balloon, Will? Have you given a moment’s thought to what’s likely to happen to those thighs of hers in the aftermath of childbirth?’ The old man stretched out in the bath, a cumulus of soapsuds covering his nakedness. Will had sat on the stool.

‘She is not petite. She is squat. She has the normal centre-of-gravity of a Mediterranean peasant, a cantilever’s equilibrium somewhere between nipple and sphincter, and you don’t even have a field to plough. Before long you’ll be copulating with a blancmange. I only draw your attention to these things because I’m your father. It’s my duty.’

‘Thanks dad.’

‘Marriage is for ever, you know.’

‘Well actually, these days…’

‘In this family it’s for ever, take it from me. I should know. Even after my unsuccessful physiological experiments to find out if your mother’s mouth might sometimes be made to close as well as open, I was still stuck with her for the rest of her natural existence. Till death us do part. Yes indeedy. Though as it has turned out nothing so trivial as mortality has been able to keep to keep Patricia off my back. Even the mild salve of growing deafness to soften the progress of the years hasn’t helped. She installed her voice inside me before departing for the Elysian fields. The drill-bit of your mother’s voice has remained unblunted. It is an unfailing internal mechanism. No wonder the Hamilton-Essleys were all smiling the day they saw their daughter wed. Not a wet eye among the lot of them. Even your maternal grandmother, tight-faced old bitch that she was, could hardly keep the smirk off her features. Marriage.’ ‘And now you have Lindsey, dad.’

‘And now you have Lindsey, dad.’

‘And now I have Lindsey.’

His father seemed to sink into meditation at the mere mention of the name. When he spoke again he seemed to be speaking largely to himself.

‘Always were a spunky lad, Will. Sometimes we needed to take a hammer to your bedsheets to get them into the washing machine in the morning. I said to your mother, the minute that boy has access to a functioning vulva, spermatazoon will be shooting through the dark like rockets on bonfire night. The ovum will soon remember its etymology and we’ll have some broody female hatching her egg. I said it more often than I can recall: the minute he’s got a full-size woman to go at, it’ll be uterus and womb all the way, you mark my words. She’ll drain him like a marsh. My little limestone dreamer.’

‘Well, thanks for the pep talk, dad. I’d always wondered when you’d fill me in on the birds and the bees.’ The son was, as usual, exhausted after a few moments in his father’s company. He uttered the next statement as though talking to himself.

‘All God’s children got wings, though.’

In an urgent whisper this: ‘So fly away then, while you’ve still got time. Don’t let some fatuous notion of duty entrap you. Is it because you’ve impregnated her? Is that it? Is the social stigma so great that returning her to the island where you found her would imperil her life?’

‘She was born and raised in Surrey, dad. And she’s not pregnant.’

‘We could find some Mediterranean nunnery where she’d be safe.’

‘Her father’s a headmaster in Esher.’

The old man had now risen to the upright position in his determination to speak his mind; bath waters were rippling in the wake of his unquiet. When he finally removed his hand from his son’s shirtsleeve, a wet print of emaciated fingers remained. He retreated stealthily beneath the waters, stretching a bony arm out for the soap as he sank.

Thus had the head of the Fenshawe family and Will’s progenitor lifted a fellow’s spirits on the eve of marriage.

Thus had the head of the Fenshawe family and Will’s progenitor lifted a fellow’s spirits on the eve of marriage. Will had neither forgotten nor forgiven. And yet the most curious thing of all was that as the marriage had progressed (was that really the right word?) Will’s quickest route to arousal with his wife had become the fantasy that she was indeed a Mediterranean peasant. Somewhere in a field in the heartlands of Sicily, crying out ceaselessly her one word of Italian, ‘Sì, sì, sì,’ as Will went to it with a vengeance. And as it turned out, his father had been right about the thighs.

When Charlie got back to Shepherd’s Cottage late that night he found Jessica waiting for him. He hadn’t invited her back.

‘I got in through the window. You left it open. I could see all the lights on in the big house.’

‘Jessica…’

‘You can call me Jess now.’

‘It took him over a minute to realise he was glad she was there. She had covered up RAW SEX. He wanted to see it again. He poured her a drink. He took the guitar from his case. He started to play.

Know my baby, she’s bound to love me some.

Yes you know my baby, she’s bound to love me some.

Throws her arms around me like a circle round the sun.

♦

—This is the fifth installment of White Ivory. —

See previously

chapters 1 & 2

chapters 3 & 4

chapters 5 & 6

chapters 7 & 8

ALAN WALL was born in Bradford, studied English at Oxford, and lives in North Wales. He has published six novels and three collections of poetry, including Doctor Placebo. Jacob, a book written in verse and prose, was shortlisted for the Hawthornden Prize. His work has been translated into ten languages. He has published essays and reviews in many different periodicals including the Guardian, Spectator, The Times, Jewish Quarterly, Leonardo, PN Review, London Magazine, The Reader and Agenda. He was Royal Literary Fund Fellow in Writing at Warwick University and Liverpool John Moores and is currently Professor of Writing and Literature at the University of Chester and a contributing editor of The Fortnightly Review. His book Endtimes was published by Shearsman in 2013, and Badmouth, a novel, was published by Harbour Books in 2014. A collection of his essays was issued by Odd Volumes, The Fortnightly Review’s publishing imprint, also in 2014. A second collection, of his Fortnightly reflections on Walter Benjamin, followed in 2018, and a third collection, Midnight of the Sublime, has just been published. An archive of Alan Wall’s Fortnightly work is here.

ALAN WALL was born in Bradford, studied English at Oxford, and lives in North Wales. He has published six novels and three collections of poetry, including Doctor Placebo. Jacob, a book written in verse and prose, was shortlisted for the Hawthornden Prize. His work has been translated into ten languages. He has published essays and reviews in many different periodicals including the Guardian, Spectator, The Times, Jewish Quarterly, Leonardo, PN Review, London Magazine, The Reader and Agenda. He was Royal Literary Fund Fellow in Writing at Warwick University and Liverpool John Moores and is currently Professor of Writing and Literature at the University of Chester and a contributing editor of The Fortnightly Review. His book Endtimes was published by Shearsman in 2013, and Badmouth, a novel, was published by Harbour Books in 2014. A collection of his essays was issued by Odd Volumes, The Fortnightly Review’s publishing imprint, also in 2014. A second collection, of his Fortnightly reflections on Walter Benjamin, followed in 2018, and a third collection, Midnight of the Sublime, has just been published. An archive of Alan Wall’s Fortnightly work is here.

Image credits.

Hölderlin’s Tower, Tübingen (Emil Klein, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons); 19th-century Grub Street (latterly Milton Street), as pictured in Chambers Book of Days via Wikimedia Commons; sketch of Ludwig Wittgenstein by Arturo Espinosa via Wikimedia Commons,“Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent”; sketch of Frank Plumpton Ramsey by Patrick L. Gallegos (2017); train image by Phil Scott, background removed (Our Phellap); wedding rings (Olga Ubirailo); bathtub (Dreamer Company).

Post a Comment