By STEPHEN WADE.

THE BOOKS, DOCUMENTARIES and magazine features marking a succession of centenaries from the Great War have almost swamped the general reader over the last few years. But there is one particular military casualty whose injury catches our attention very powerfully: the blind Tommy. Central to the imagery of these men is arguably John Singer Sargent’s painting, ‘Gassed’ which shows a line of soldiers, each with his arm out towards the man in front, and each resting a hand on his colleague’s shoulder. This particular notion, of a line of helpless men, also figures in the artwork outside Piccadilly Station in Manchester, and in a photograph showing men ‘blinded by tear gas’ which has appeared in the mass media.

The question arises about what was done to help these servicemen at the time and in the post-war years? Quite a lot was done, and two names stand out as pioneers in this respect: Sir Arthur Pearson and Georges Scapini.

The question arises about what was done to help these servicemen at the time and in the post-war years? Quite a lot was done, and two names stand out as pioneers in this respect: Sir Arthur Pearson and Georges Scapini.

Sir Arthur Pearson was the man who founded the Daily Express, when it began as a halfpenny paper in 1900. He was an ambitious and formidable businessman, born in Wookey, Somerset in 1866, the son of a Buckinghamshire rector, and a man who loved entering quiz competitions. It was by winning one of these that gained him his first publishing job, working as a clerk for the prototype mass-market periodical, Tit-Bits — from all the interesting Books, Periodicals, and Newspapers of the World. In 1914, on the occasion of the eighteenth annual general meeting of C. Arthur Pearson Ltd., at the Savoy Hotel, Pearson told his colleagues: ‘ I need not go into the figures in detail, but it is with considerable satisfaction that I would point to the fact that the profits show a material increase on those of last year.’ They were doing very nicely, thank you.

Pearson’s empire had also formed a working alliance with that other baron of the press, George Newnes, one of Conan Doyle’s principal publishers. The new alliance, he said, had led to considerable improvements. The two massively powerful press entrepreneurs, Newnes and Harmsworth (later Lord Northcliffe), had created many of the publications which kept hundreds of freelance writers in regular work; back in 1896, Arnold Bennett saw the two men at the Haymarket Theatre and he wrote that they were ‘… chiefs of the two greatest popular journalistic establishments in the kingdom, each controlling concerns which realize upwards of £100,000 net profit per annum.’

Pearson’s empire had also formed a working alliance with that other baron of the press, George Newnes, one of Conan Doyle’s principal publishers. The new alliance, he said, had led to considerable improvements. The two massively powerful press entrepreneurs, Newnes and Harmsworth (later Lord Northcliffe), had created many of the publications which kept hundreds of freelance writers in regular work; back in 1896, Arnold Bennett saw the two men at the Haymarket Theatre and he wrote that they were ‘… chiefs of the two greatest popular journalistic establishments in the kingdom, each controlling concerns which realize upwards of £100,000 net profit per annum.’

Then, at the end of his speech, Pearson commented on the one factor in his life that made him stand out in terms of his nature and his work. He said simply, ‘I am just as keenly interested in the progress of the company with which my name is identified…though I am blind.’

In fact, earlier in life Pearson had worked for Newnes, and as soon as he was successful on his own, his philanthropic nature expressed itself: he established a charity called the Fresh Air Fund, to help disadvantaged children. His eyesight problems increased his awareness that his wealth could help others who had disabling conditions.

At the turn of the century he was the kind of press magnate who thoroughly backed and revelled in the spirit of exploration and adventure which formed the basis of so much of his friends’ fiction. One of these ventures led to the massively popular series of reports in the Express from the explorer Hesketh-Pritchard in Patagonia. But Pearson was a writer in his own right, producing works related to many popular subjects, and in this there came his criminological interest: graphology. Today, he would surely have been keen on forensic linguistics; his book, written under the nom de plume of ‘Prof. Foli,’ Handwriting as an Index to Character was published just a year before the first meeting of the Crimes Club, a group of amateur sleuths and criminologists which included Conan Doyle. His opinions would have coincided with some of the work being done in criminology by Bertillon and Cesare Lombroso, as being yet one more method by which individuals could be located and described.

At the turn of the century he was the kind of press magnate who thoroughly backed and revelled in the spirit of exploration and adventure which formed the basis of so much of his friends’ fiction. One of these ventures led to the massively popular series of reports in the Express from the explorer Hesketh-Pritchard in Patagonia. But Pearson was a writer in his own right, producing works related to many popular subjects, and in this there came his criminological interest: graphology. Today, he would surely have been keen on forensic linguistics; his book, written under the nom de plume of ‘Prof. Foli,’ Handwriting as an Index to Character was published just a year before the first meeting of the Crimes Club, a group of amateur sleuths and criminologists which included Conan Doyle. His opinions would have coincided with some of the work being done in criminology by Bertillon and Cesare Lombroso, as being yet one more method by which individuals could be located and described.

In 1912, as his glaucoma became more severe, Pearson scaled down his involvement in newspapers; an operation on his eyes in 1908 had not had much effect, and he gradually stepped back from his business, with Max Aitken (later Lord Beaverbrook) taking over at The Daily Express. There was more time available for Pearson to busy himself with projects related to helping the blind. By 1914, when the enormous number of British Tommies affected by damage to their eyes in the war became an urgent issue for society, he established St Dunstan’s home for blind service personnel. Two years before the war, he produced his Pearson’s Easy Dictionary, which was in Braille form. It was a marked success during the Great War, as not only St Dunstan’s but the regional military hospitals (such as the Beckett Park Hospital in Leeds) catered for the war casualties. Numbers of injuries increased as gas began to be used, and for women, there were dangers in their munitions work.

In 1912, as his glaucoma became more severe, Pearson scaled down his involvement in newspapers; an operation on his eyes in 1908 had not had much effect, and he gradually stepped back from his business, with Max Aitken (later Lord Beaverbrook) taking over at The Daily Express. There was more time available for Pearson to busy himself with projects related to helping the blind. By 1914, when the enormous number of British Tommies affected by damage to their eyes in the war became an urgent issue for society, he established St Dunstan’s home for blind service personnel. Two years before the war, he produced his Pearson’s Easy Dictionary, which was in Braille form. It was a marked success during the Great War, as not only St Dunstan’s but the regional military hospitals (such as the Beckett Park Hospital in Leeds) catered for the war casualties. Numbers of injuries increased as gas began to be used, and for women, there were dangers in their munitions work.

At St Dunstan’s, first based in Regent’s Park, the blind men and women became known as Pearson’s New Blind Army, and by 1919 around 1,500 men had learned new skills there in the workshops. Many were very young of course, and the aim was to rehabilitate them into civilian life if possible; a range of activities was on offer, from basket-weaving and boot repairs to sports. But a basic instruction in Braille was the core, and Pearson’s dictionary was a standard for the course.

NOTE: In The Fortnightly’s online template, illustrations are thumbnails with captions or onward text links embedded. To enlarge an illustration, click on it. To read a caption, hover over the illustration. To play an embedded video in a larger size, click twice.

The government had to react to the very high level of disability in the armed forces, and while care in any one of the dozens of stately homes converted to military hospitals was a first stop, support such as a full pension for loss of sight cases, and then special treatment at places such as St Dunstan’s followed wherever possible.

Pearson was always pleased to help and promote his cause, and on one occasion he went to meet a young solder invalided home to present him with a Braille watch. It may have been a useful PR moment, but from Pearson, everything was genuine.

St Dunstan’s did very well indeed, developing through the twentieth century into an important part of general rehabilitation after injuries arising from theatres of war. In 2012 it transmuted into Blind Veterans UK.

Pearson fell and was drowned in his bath in 1921. After his death, aged only 53, thousands attended his funeral at Hampstead cemetery on 13 December, 1921. A guardsman led a long line of blind mourners through the cemetery, and the union jack over his coffin had his slogan, Victory over Blindness, written on it.

♦

IN CONTRAST, GEORGES Scapini, a Frenchman celebrated in his country in similar terms to Pearson in Britain, was an individual, but not an entrepreneur. He was a barrister, born in 1893. After his horrendous wartime experience, he wrote a memoir, L’Apprentissage de la Nuit [Apprenticeship to the Night]. This was noticed by the hugely successful essayist, E.V. Lucas, who included a piece on Scapini in his 1931 collection, Traveller’s Luck. Here, he wrote, ‘M. Scapini’s message is that ‘the night’ [his metaphor for his blindness] need not engender despair. He is now not yet forty, and it will be of absorbing interest to see what the future has in store for him.’

The future had great things in store. He was to become the president of France’s central organisation for the assistance of blinded service people, L’Union des Aveugles de Guerre, a charitable organization established in 1901. As with St Dunstan’s, the Union provided training in a range of crafts and skills, with finance being found for workshops and to fund tutors.

Scapini, Lucas wrote, overcame his handicap to such an extent that he could ride and swim, use a typewriter and enter the French Chamber of Deputies. He was wounded twice in the Great War during his first spell in action; these injuries were in his legs. But when he returned to the front, at Ermenonville he received the serious wounding which was to blind him. The report of the action he saw at that encounter stated that he was ‘grievously wounded’ while staunchly defending a barricade against a violent assault. He was awarded the Medaille Militaire, presented to him by Marshal Joffre, and after that he set about doing something constructive to help others in the same plight.

Scapini, Lucas wrote, overcame his handicap to such an extent that he could ride and swim, use a typewriter and enter the French Chamber of Deputies. He was wounded twice in the Great War during his first spell in action; these injuries were in his legs. But when he returned to the front, at Ermenonville he received the serious wounding which was to blind him. The report of the action he saw at that encounter stated that he was ‘grievously wounded’ while staunchly defending a barricade against a violent assault. He was awarded the Medaille Militaire, presented to him by Marshal Joffre, and after that he set about doing something constructive to help others in the same plight.

Scapini went on to parallel the work of Pearson, primarily in his time as President of the Union. Unlike Pearson, he had more time to do different things, including being the (blind) ambassador to Germany for his country between 1940-1944. He ran into trouble, accused of offering some kind of aid to Germany, and served ten months in prison at one time, followed by a sentence of hard labour in his absence in Switzerland, but this was quashed when he returned home and faced a tribunal. During his time working with the blind, a similar system of workshop provision was effected in France, along with the Braille instruction which was necessarily a foundation for all the work.

He died in Cannes in 1976, aged eighty-two. His striking image is there above his grave: a man whose face is lined and weary, with his distinctive patch over his left eye. L’Apprentissage de la Nuit, wrote Lucas, was ‘… a triumph for blindness as well as for its author. But far more – and this is its great value and recommendation – it is an encouragement to those similarly afflicted.’

What both Pearson and Scapini realised- and acted upon – was that the ‘despair’ Lucas wrote of, was not insurmountable. One of the secrets of success in this respect was the kinship and the support systems among those afflicted. Life could go on.

♦

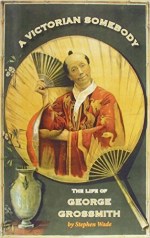

Stephen Wade is a writer and historian. His latest books are The Justice Women (Pen and Sword), which is a history of women in all areas of the law; No More Soldiering (Amberley), which looks at the conscientious objectors of the Great War; and Rejected: Literary failure and my contribution to it, published by us as part of our Odd Volumes series. He has also previously written for the Fortnightly on the subject of George Grossmith (see ‘Entertaining Mr Pooter‘).

Stephen Wade is a writer and historian. His latest books are The Justice Women (Pen and Sword), which is a history of women in all areas of the law; No More Soldiering (Amberley), which looks at the conscientious objectors of the Great War; and Rejected: Literary failure and my contribution to it, published by us as part of our Odd Volumes series. He has also previously written for the Fortnightly on the subject of George Grossmith (see ‘Entertaining Mr Pooter‘).

Post a Comment