By STEPHEN WADE.

Sixth in a series.

TRADITIONALLY, IN WORLD LITERATURE, the best way to minimise rejection was to find a patron. If the aspiring bard could find a Milord, a sovereign or at least the CEO of a great business, then the future was rosy. That is, if the bard in question could write praise with a special kind of greasiness. There were various gambits here. If the Mighty One was ugly in every respect but in his speech, say, then the thing to do was to ignore the nose as big as a shed and the bags under the eyes like sacks and the dribble from his slobbering mouth, and produce something like this:

Lord Butterfield excels, best in all, north, east, west and south,

For he has the most glorious, silver words spilling from his mouth.

Or, if total obsequious toadying was required (which was the case if the bard was heavily in debt and faced a spell in prison) then everything could be praised, shamefacedly, thus:

Bound for greatness is my Lady Farthingworth-cumber;

Beauteous is she, especially in slumber;

Though, when awake, her smile beguiles;

Men come to worship, from a hundred miles.

An epic could I pen merely upon her hair;

To be absent from her, I cannot bear.

Now, this is doggerel, but the point is that doggerel is exactly what was required. If too much talent were displayed to the would-be patron, then it could be concluded, what need was there of help?

ASPIRING POETS PRACTISED in front of the long mirror in the coffee house, developing the expressions of crawling, creeping and applying oleaginous words of compliment and praise. But all that was for a purpose- to please someone called a dupe, a gull, someone so thick that they would shower money on any spotty rhymer who could look artistic and pout a little.

However, in the Age of Reason, when patrons were only too happy to gather poets and writers, the poor poet had to be seen and helped at the levee. This was a cultural tradition designed especially to humiliate every failed, scrounging cur of a scribbler who had fallen on hard times and needed a bag of silver. The idea was that, as Milord or Milady emerged from their rooms of a morn, a line of bending, hat-tipping, slavering toadies would offer their services. It was an age of sinecures, so that Milord might think that the pathetic, fleshless, starving garret-dweller working on an epic about Roderick the Goth (see Southey, above) might do very well in the position of Hermit of the Estate. This was a wonderful position for the needy bard: he simply had to sit in a grotto on the newly improved lands of the Milord and be observed by parties of visitors. He simply had to bow his head and start writing a sonnet as soon as a gaggle of culture-vultures came in sight of his den.

However, in the Age of Reason, when patrons were only too happy to gather poets and writers, the poor poet had to be seen and helped at the levee. This was a cultural tradition designed especially to humiliate every failed, scrounging cur of a scribbler who had fallen on hard times and needed a bag of silver. The idea was that, as Milord or Milady emerged from their rooms of a morn, a line of bending, hat-tipping, slavering toadies would offer their services. It was an age of sinecures, so that Milord might think that the pathetic, fleshless, starving garret-dweller working on an epic about Roderick the Goth (see Southey, above) might do very well in the position of Hermit of the Estate. This was a wonderful position for the needy bard: he simply had to sit in a grotto on the newly improved lands of the Milord and be observed by parties of visitors. He simply had to bow his head and start writing a sonnet as soon as a gaggle of culture-vultures came in sight of his den.

Yet, it is sad to relate that there were dozens if not hundreds of rejected scribes in the levees also. They were doomed to grovel and be rebuffed, as was their condition. The stories of such unwanted creative types are legion, but one stands out: the case of the poor Elizabethan poet, Thomas Bastard. Not only was he cursed with that name: he failed to be noticed after years of hard networking, then published one collection with a name that no-one could pronounce, Chrestoleros, in 1598. He was destined to fail, being made a Fellow at Oxford, and then having that taken away as he was charged with libel. Thomas died in a debtors’ prison in 1618.

Yet, it is sad to relate that there were dozens if not hundreds of rejected scribes in the levees also. They were doomed to grovel and be rebuffed, as was their condition. The stories of such unwanted creative types are legion, but one stands out: the case of the poor Elizabethan poet, Thomas Bastard. Not only was he cursed with that name: he failed to be noticed after years of hard networking, then published one collection with a name that no-one could pronounce, Chrestoleros, in 1598. He was destined to fail, being made a Fellow at Oxford, and then having that taken away as he was charged with libel. Thomas died in a debtors’ prison in 1618.

Dr Johnson, that great literary hero, was one of the first to pinpoint the source of rejection: critics. In Johnson’s day, it was not too difficult to be in print. One simply wrote a poetry collection- on something scurrilous and cheeky but not actually seditious- took it to a bookseller around St. Paul’s, and there you are, he would print it and give you a flat sum. There were no royalties, but that few pounds would feed you in your garret for a week or two. The booksellers were also publishers. The only problem was that lots of writers did not produce poems. Then, as now, they produced unsellable scribblings which would not attract the potential customers browsing in the old shops in between coffee-house meetings and trips down Gin Lane.

The normal unsuccessful negotiation went something like this:

Writer: Sir, necessity compels me to offer you my sermons, written from the bottom

of my heart.

Bookseller: Necessity Sir? Why, are you hard-pressed? Your attire is a trifle distressed.

Writer: Sadly, I lost my living.

Bookseller: Then you are technically erm…dead.

Writer: No dear Sir, I mean I was a parson.

Bookseller: And you wish to sell your sermons to be able to eat.

Writer: You have it precisely.

Bookseller: Sorry old chap. Too many sermons stuck on the shelf. We live in

Godless times. People don’t want to be preached at.

Writer: Preached? Oh dear me…well I can take out the preaching and put in

lots of sex and violence.

Bookseller: How much? We’ll have to change the title. I mean One Step from Hell

will drive people away.

Writer: What about One Step from Hell: a guide to London’s Sodom?

Bookseller: Fifty quid! Shake on it?

IN THE SO-CALLED Augustan Age – the early eighteenth century — authors became something reasonably close to what they are now: hard up, desperate and alone. But they could add that word to themselves and set up a stall, or at least a desk, somewhere in a tiny attic or cellar, and work day and night. The profession of jobbing scribbler became a possibility, and we are fortunate that the diary of one such early literary man has come down to us. This is the work of Abraham Poges, epic poet and social nuisance.

Poges knew failure – and he knew it in a world in which creative talents who could not secure a leg up into society tended to sink into a Hogarthian pit of offal, rats and rejected manuscripts. He lived and slept with failure; he gnawed at the bones of rejection like some starveling pauper thrown out of the parish. He was, unknown to himself in fact, the Muse of Rejection, doomed to struggle for the crumbs of the booksellers.

Professor Sludge, the man who rescued Poges’ work from oblivion, has kindly contributed this preface to the extracts from the writer’s journal:

ABRAHAM POGES’ BOOK

Being the journal of an Augustan scribblerPreface

By Dr. Norbert Sludge D.Litt.It is not often that works of literary genius come to light in today’s utilitarian world, but here we have that rare thing – a true ‘find’. I now know what it is to trail one’s fingers nervously over the yellowing pages of an aged manuscript book – a volume unopened since the writer quit the world and all its struggles. (My partner, Geronimo, was very patient and put up with the odours.) Of this now classic outpouring of Augustan literary Angst and scribbler’s war very little is known, and the writer, too, is clouded in obscurity. Johnson never dined with him, nor Boswell tapped him for a loan. All we know about Poges is that he was born in obscurity, in Kent or perhaps in Cumbria or perhaps in Norfolk, and that he was rumoured to have been left to the whimsical mercies of a wet-nurse, rejected by his parents. Why, we know not. Otherwise, we know what is between these covers. I have been able to find only one reference to him in a contemporary biographical work:

Poges, Abraham. A tiny scribbler of trivial love verses and very pretentious epic tales in the manner of every great writer who ever lived. Wrote his first book, an epic in rhyming couplets, at the age of ten. Shunned in coffee houses by all discriminating critics. Perhaps best remembered as the power behind the actress, Jenny Jigger.’ This is all we have, but for a scrap I have traced in a musty volume of Notes and Queries in which a writer of Roman tragedies wrote of Poges, ‘ Went t’other day to sit with Poges, and was driven from his company by the noxious stench of his body sweat. He has, I aver, not seen the inside of a bath-tub for some months, nor perhaps since he was a babe…’

I leave the reader to decide how much merit there is in this poor man’s posthumous writings. All I know is that, though he will never know it, simple Poges has provided me with academic success, since that momentous day in an rotting old bookshop in a market town, I saw the battered tome and read those fateful opening words about one of his notable ailments. His body failed, as his writing did too, poor man.

Yet scholarly works have proliferated now. I append a short bibliography. Poges’ works are out of print, but I hope that some smart publisher will soon remedy this.

10th. Nov. 1758

Had terrible agony with the pendulous, bulbous protrusions in my backside today. They did throb most mightily and interrupted my labour with the most sublime work of poetry the world has ever seen. I know that this time I have it – the perfect epic plot. It came to me as I wiped the grease from my collar at table. In haste I departed from the board and began a summary of the magnum opus. ‘Tis to be called, Grubbius in Oblivion and tells the epic of an unknown, bespotted and rag-covered hack with his Hebrew of a bookseller. To win the respect and service of Tobin, a bespectacled, incestuous rogue with a passion for the flesh of insects, Grubbius has to prove worthy of the bibliophile’s beauteous daughter, Wimple, and Grubbius must endure six trials of his worth. These are:1. Hurling of the bucket of ink. Here, Grubbius has to throw, with vigour, a two-gallon pail of ink across a wide chasm without one spot of liquid settling on an amused crowd of clergymen in white surplices at the valley bottom. The hero trains by drinking strong ale and abstaining from commerce with nought but lads for seven weeks together. (Seven being a magick number, Grubbius having seven nipples it was said). At the end of the trial, the Yorkshire sheep close to the chasm do suffer mightily after Grubbius’ ascetic life.

2. Going without gin for a week. A most gruelling demand. He sweats like a pigge.

3. The attendance at St. Agrippa’s school as usher for a term. In which our hero is waylaid by sundry unruly scholars.

4. The cleansing of Lord Gout’s stables. The classical theme will make me out a scholar. In which Grubbius allows the waters of the cesspool to free the stables of clotted dung, yet the foule stinke thereof does wax most terrible noxious to the snout and orbs.

5. The duel with Sir Jittering Crimp. In which G. receives some ventilation of an bigge-bone in the leg due to the rapid passing-through thereof of a massy agglomeration of buckshot metals.

6. The final labour is, to Wimple, the Lady of the Becke, most dear. Here G. must ope the door to her chamber using nought but his wide and sturdy shoulders. The door is passing thicke and severe bruises are sustained yet G. lives on, unable to gratify his carnal desires for some months. What think ye, reader of time to come? Am I vain? Do I suffer from the vanity of fine writers? God bless the mark!

On the morrow I take my great plan to Jacob in St.Paul’s Churchyard. ‘Tis worthy of a guinea and so to do a few hours in the coffee house and mayhap the purchase of a wench. A thought enters my pate – is not Grubbius something of myself? Yea great Milton writ ‘On his blindness’ – then why not Abe Poges in like manner reveal himself?

By the by, young Jenny at the druggists would not yield – again. The little bauble plays coy with me. That small closet behind the shelf is most suitable for the seduction, yet she EVEN NOW will not be cajoled. Egad, I still have mine own hair and teeth and not turned forty years and two yet! Does the maid abhor me? ‘Tis my perfume mayhap. Too much rubbed around my wet member? I must try the fortress yet again – this time with more compendious strength in the army. I shall have her and be content.

Mayhap ‘tis the smell of my hands. I have a particular essence dwelling there that art and craft cannot remove. How many times have I essayed the use of potions and unguents to shift that stench. Yet it will persist. My sister, Wrestling Soul Poges, accounts it to my youthful habit of avoiding clean water.

Addendum: Not to forget to call in at Rayworth’s Chocolate House as that foul Johnson is guaranteed not to be there. Whenever he spies me, the great bulk never misses the opportunity of railing and teasing at me for the farce of my one theatrical work. I wish he would choke on his steak -–and by God, why can’t he stop his face from twitching? In his company, I will start to twitch also, in counterpoint. I suppose he was quite good once – after all, he did write that tedious dictionary.

11th. Nov. 1758

The manuscript was completed this day but hell followed. Ye Gods! Today was the worst day of my life. Delays and tribulations pursue me like a pack of hungry curs chasing the fox. I am a hunted man and fate is in pursuit. Did Genius ever bear such pangs? The day began ill, when I spewed mightily upon rising from bed, and my pate overhung the tub for close on one hour. My good landlady, Mrs. Turtle, did wax most satirical. She did aver that filling my maw with Muscadel and delicacies was the cause. Yet surely a man – a literary man to boot – needs the sensual gratification of a good piece of hoggery from time to time. Nothing tempts the lips more than a slice of seed cake or a joint of lamb.Well, there was I in my nethers when Mrs. Turtle ‘ gins to snigger most rudely at my plight. I was owing three weeks’ rent, else she would have received a bowl of piss in her visage.

Worse was to come, for on sitting at my desk, I discovered that the papers on which I writ my Epic Prologue had vanished. Imagine my plight. This was the opus which was to take my name into every literary weekly in the City, and it had gone. Mrs. Turtle vowed she had not lighted the fire with them, and so a search began, and egad, if the cat had not taken them to have her kitlings on! So Mrs. Turtle claimed. The tabby whore has been with kitling for two dozen times, I swear. The sides of nature will not sustain it, as the Bard says.There was the bloody sludge and the squealing things mewling most piteously. My heart would have gone soft is ‘twere not for the huge difficulty in distinguishing the letters of my masterpiece that lay beneath, besmirched.

13th. Nov. 1758

By Saint Hugh, the great work was copied out again, and finally delivered to the bookseller. He’ll see its genius at once. He cannot resist my words, the exquisite form, the sublime rhyming…This is my time. The world will see me for the genius I am. No long will my bushel be under the light, or my light under the bushel. (Note to self: what is a bushel?)14th. Nov. 1758

The manuscript was returned. I say that boldly, like a man. But inwardly I weep like a scolded child. The bookseller’s lad delivered it, and sniggered as he threw it into my cellar.

May all publishers and their minions die slowly, of the plague!

Hacks like Poges infested the East End, and many had the fate of chewing on leather and going raving mad after finding that their sermons or their huge epic poems were ‘not commercial.’

As time went on, and writing became more sophisticated, writing was seen as a branch of mental derangement, as Robert Burton, the specialist in insanity, knew, and he put it simply: ‘All poets are mad.’

Shakespeare, in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, agreed:

The lunatic, the lover and the poet,

Are of imagination all compact.’

The professionalization of rejection took a long time to mature.

However, sympathy in this respect was rare indeed. There is no record of a publisher ever saying to his colleagues, ‘Whatever you do, don’t reject poor Tom Toddle’s work… he’ll top himself!’ The professionalization of rejection took a long time to mature.

This is a rough summary of how the language and attitudes developed and changed:

Dark Ages: Your poem is shit.

Medieval: Poor stuff. Go be a ploughman

Tudor: Write that again and I’ll cut your hand off.

Stuart: Say the king is great and I’ll reconsider

Augustan: Inferior drivel, old man. Light the fire with it.

Georgian: The divel take it, I won’t!

Victorian: We most reluctantly decline to accept your manuscript.

Twentieth Century: Not this time, Mr Smith.

Contemporary: Sadly, this does not fit with our current lists, go brand yourself.

In the time of wigs, duels and fifteen-course dinners, those in search of patrons were not always poetasters, pretenders and tender wilting souls. Take Jean-Louis de Lolme for instance. He is the author of a standard work on British politics: Constitution of England. This finally found print in 1771 and is now recognised as a classic work on the English political system and liberty, with an analysis of the Separation of Powers. But poor de Lolme was widely rebuffed. As Isaac D’Israeli, father of the Prime Minister Benjamin, wrote of this struggling author:

In the time of wigs, duels and fifteen-course dinners, those in search of patrons were not always poetasters, pretenders and tender wilting souls. Take Jean-Louis de Lolme for instance. He is the author of a standard work on British politics: Constitution of England. This finally found print in 1771 and is now recognised as a classic work on the English political system and liberty, with an analysis of the Separation of Powers. But poor de Lolme was widely rebuffed. As Isaac D’Israeli, father of the Prime Minister Benjamin, wrote of this struggling author:

The fact is mortifying to record, that the author who wanted every aid, received less encouragement than if he had solicited subscription for a raving novel or an idle poem. De Lolme was compelled to traffic with booksellers for this work; and as he was a theoretical rather than a practical politician, he was a bad trader…He lived in extreme poverty and decay… He never appears to have received a solitary attention, and became so disgusted with authorship that he preferred silently to endure its poverty rather than its vexations.’

Still, after using the subscription method, his great work finally saw print.

Even Dr Johnson had problems with his patron, Lord Chesterfield. Johnson planned to write his great Dictionary of the English Language (1755) using no more than his own efforts and a team of scribes, working in his attic off Fleet Street. Chesterfield promised much but tended to forget and Johnson was never in his mind, other than receiving a payment of ten pounds. The result was that, as the magnum opus was completed, he wrote to Chesterfield, asking: ‘Is not a patron, my Lord, one who looks with unconcern on a man struggling for life in the water, and when he has reached ground, encumbers him with help?’

Consequently, the definition of a patron in the great dictionary was: ‘ One who countenances, supports or protects. Commonly a wretch who supports with insolence, and is paid with flattery.’

♦

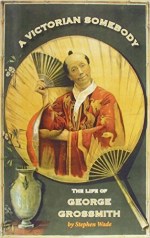

Stephen Wade is a writer and historian. His latest books are The Justice Women (Pen and Sword), which is a history of women in all areas of the law, and No More Soldiering (Amberley), which looks at the conscientious objectors of the Great War. He has previously written for the Fortnightly on the subject of George Grossmith: see ‘Entertaining Mr Pooter‘.

Stephen Wade is a writer and historian. His latest books are The Justice Women (Pen and Sword), which is a history of women in all areas of the law, and No More Soldiering (Amberley), which looks at the conscientious objectors of the Great War. He has previously written for the Fortnightly on the subject of George Grossmith: see ‘Entertaining Mr Pooter‘.

Note: This essay is part of a series on ‘literary rejections’.

Post a Comment