By STEPHEN WADE.

Fourth in a series.

THE BASIC MISSING faculty which may be absent in failed writers is talent. Arguably, the main barrier to attaining that is a quality of dullness. The snag is that a poet may be dull and not know it. That’s why critics exist. Though they may also be dull, so other critics are needed to tell them. But these critics may be dull so…That’s why we have literary theory.

THE BASIC MISSING faculty which may be absent in failed writers is talent. Arguably, the main barrier to attaining that is a quality of dullness. The snag is that a poet may be dull and not know it. That’s why critics exist. Though they may also be dull, so other critics are needed to tell them. But these critics may be dull so…That’s why we have literary theory.

By the eighteenth century, as the great Alexander Pope reminded everyone, dullness in writers found a new low. In that great age of satire, there was undoubtedly a glut of mediocre talent amongst the scribblers. Most of them tried very hard to make their way in the world by writing in praise of anything they happened to come across, such as :

Oh tender trembling tippling tiny trotter

I hate to eat you but I gotta

Or perhaps they published poems to their friends, or at least, celebrities with whom they wanted to be friends, so that they could pretend they were successful:

Jack! Great bard of the west country, with a muse of fire,

I salute thee and thy noble verse, tho’ my own attempts are dire…

The absolute masters of dullness found that they had a fame of sorts, as they were the target of much ridicule. Outstanding among these alleged inadequates were Colley Cibber and Thomas Shadwell. Cibber, well published, and quite a force in the theatre of his time (he lived from 1671-1757), was nevertheless thought to be hopelessly mediocre. He was deeply involved in the scraps and backbitings in the literary world of his time, and sadly, his verse has failed to inspire, and is not far behind the great McGonagall in flatness:

The absolute masters of dullness found that they had a fame of sorts, as they were the target of much ridicule. Outstanding among these alleged inadequates were Colley Cibber and Thomas Shadwell. Cibber, well published, and quite a force in the theatre of his time (he lived from 1671-1757), was nevertheless thought to be hopelessly mediocre. He was deeply involved in the scraps and backbitings in the literary world of his time, and sadly, his verse has failed to inspire, and is not far behind the great McGonagall in flatness:

Tho’ rough Seligenstadt

The harmony defeat,

Tho’ Klein-Ostein the verse confound

Yet, in the joyful strain

Aschaffenburgh or Dettingen

Shall charm the ear they seem to wound

These noble lines are from his poem, ‘Air.’

Shadwell, however, was hammered mercilessly for his failure to impress by the poet John Dryden in the seventeenth century. Dryden conceived of a Kingdom of Dullness, with MacFlecknoe as the King in need of an heir, so enter Thomas Shadwell: ‘ In prose and verse, was owned, without dispute/ Through all the realms of nonsense, absolute.’ Dryden builds up to a template description of the poet failed through fatal dullness:

Shadwell, however, was hammered mercilessly for his failure to impress by the poet John Dryden in the seventeenth century. Dryden conceived of a Kingdom of Dullness, with MacFlecknoe as the King in need of an heir, so enter Thomas Shadwell: ‘ In prose and verse, was owned, without dispute/ Through all the realms of nonsense, absolute.’ Dryden builds up to a template description of the poet failed through fatal dullness:

Shadwell alone my perfect image bears,

Mature in dullness from his tender years:

Shadwell alone, of all my sons, is he

Who stands confirmed in full stupidity.

The rest to some faint meaning make pretence,

But Shadwell never deviates into sense.’

THIS WAS THE great age of the coffee house wits, when cliques and gangs gathered, keen to denigrate any perceived upstart. We might imagine a new aspiring poet on the scene, creeping into his corner seat, with full wig on his pate, lace-trimmed coat, and slim book of verse in hand, being observed by two war-horses of the literary world:

SCENE: Blind Todd’s Coffee House, 1700

Scoff and Tease sit in their usual seats by the fire, people-watching.

Scoff: Look, my friend. ‘tis that new bumpkin, thinks he’s the bee’s knees.

Tease: See how he pouts… beware, he may stand and read his latest ode!

Scoff: Heaven forfend! I heard he has a stutter.

Tease: (loudly) S…s… surely not my old f…f…friend Scoff?

Scoff: ‘Tis said he has bedded Lady Spreadham and so he rises…

Tease: Hah! Rises you say? Methinks the upstart has no juice in him.

Scoff: Wait… he has seen us. Observe that wicked stare.. and he now turns up his nose.

Tease: He never will climb to fame… Lady Spreadham has slept with a hundred Coxcombs…

Scoff: Wait… who is this?

Enter John Dryden, who walks to the new poet and shakes his hand.

Tease: My eyes deceive me my old chum… Dryden warms to him!

Scoff: Surely he has not slept with Dryden. The man’s straight as a carpenter’s rule.

Tease: You think so? Think again. How do you think I got my pension from the King?

Scoff: What’’’ stab me vitals! You have a pension from the King?

Tease: Yes, two hundred smackers… did not I tell you?

Scoff: No… damn you, Tease, I’m going to sit with Dryden’s lot….

Classic Rejection

ROBERT SOUTHEY TO CHARLOTTE BRONTE

OF ALL THE Bronte sisters, Charlotte was the one who pushed to achieve publication. The three sisters, Charlotte, Emily and Anne, sat around the broad table in the Haworth parsonage while father Patrick amused himself with memories and guns across the hall. The sisters were eventually to find print, at their own cost, in the volume Poems by Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell, which arrived at the parsonage on 7 May 1846 and caused a great thrill. Their need to have male identities as writers was unfortunate but essential in those benighted times for women poets.

Ten years before, with the dream of publication in her mind, Charlotte had written to Robert Southey, one-time romantic radical and now a comfy, establishment character who had accepted the laureateship. Charlotte wanted his opinion of her work, and the reply included these words: ‘ ‘Literature cannot be the business of a woman’s life and it ought not to be. The more she is engaged in her proper duties, the less leisure will she have for it…Write poetry for its own sake, not in a spirit of emulation and not with a view to celebrity.’

Ten years before, with the dream of publication in her mind, Charlotte had written to Robert Southey, one-time romantic radical and now a comfy, establishment character who had accepted the laureateship. Charlotte wanted his opinion of her work, and the reply included these words: ‘ ‘Literature cannot be the business of a woman’s life and it ought not to be. The more she is engaged in her proper duties, the less leisure will she have for it…Write poetry for its own sake, not in a spirit of emulation and not with a view to celebrity.’

She was shocked and rocked, so much that she wrote back: ‘ At the first perusal of your letter I felt only shame and regret that I had ever ventured to trouble you with my crude rhapsody…I trust I shall never more feel ambitious to see my name in print.’ Oh yes? Well, Mr Southey, who reads your poem ‘Roderick the Last of the Goths’ today when they can open the pages of Jane Eyre and be sucked into a mesmerising story of a woman in search of her true self?

Today, the reader wants to give Southey a slap. That may seem extreme, but how dare he? The sad fact is that he was of the establishment, that magical, powerful elite who run the literary pages and awards, decide on the next big thing and control the review pages.

♦

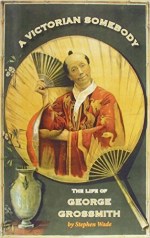

Stephen Wade is a writer and historian. His latest books are The Justice Women (Pen and Sword), which is a history of women in all areas of the law, and No More Soldiering (Amberley), which looks at the conscientious objectors of the Great War. He has previously written for the Fortnightly on the subject of George Grossmith: see ‘Entertaining Mr Pooter‘.

Stephen Wade is a writer and historian. His latest books are The Justice Women (Pen and Sword), which is a history of women in all areas of the law, and No More Soldiering (Amberley), which looks at the conscientious objectors of the Great War. He has previously written for the Fortnightly on the subject of George Grossmith: see ‘Entertaining Mr Pooter‘.

Note: This essay is part of a series on ‘literary rejections’.

Post a Comment