Sanction, pragmatic pursuit and civil society in Trollope’s The Eustace Diamonds.

By ANDREW R. LALLIER.

“Lucy, do give me that hunchy bit” said Nina.

“Hunchy is not in the dictionary,” said Cecilia

“I want it on my plate, and not in the dictionary” said Nina. (171)

THE ABOVE PASSAGE is easy to miss, being a short exchange between two relatively minor characters (two of Lady Fawn’s daughters) and apparently little more than a momentary diversion from the main action of Lucy’s reception of Frank Greystock’s fateful letter. An attentive reader of our own time might pause for a second in vague appreciation of the Lewis Carroll-like joke being played, but would be unlikely to proceed much further. Nevertheless, the distinction drawn here goes well beyond this exchange, informing the form and content of The Eustace Diamonds, and bearing directly on its articulation of the law, custom and force. At first glance, Nina is distinguishing between the say-able and the do-able: while hunchy may not technically be a part of the English Language, one may certainly take a knife to the bread and extract the desired bit. Yet ‘hunchy’ is a word – a word that, as Nina demonstrates, can possess an effective reality: it can designate in a way that permits both recognition and action. More precisely, then, Nina distinguishes between what is officially articulable (what is in the dictionary, and therefore counts as proper English), and what may be said and done beyond the realm of official sanction. Nina is perfectly content to let the dictionary stand guard over what counts as acceptable language, but refuses to let this function impede her ability to possess and consume the desired object. Nina’s distinction opens up a gulf that runs throughout this novel, between the realm of the sanctioned (whether in legal code that, like the dictionary, is supposed to provide linguistic-material force, or in the less explicit but no less potent realm of custom) and the pragmatic field of what characters can actually say and do, especially in pursuit of self-interest and acquisition. Although the most forceful illustrations of this gulf occur around the disruptive figure of Lizzie Eustace, the more amiable Lucy testifies to the gulf’s presence as well, and its effects can be felt throughout the social field of the novel.

THE ABOVE PASSAGE is easy to miss, being a short exchange between two relatively minor characters (two of Lady Fawn’s daughters) and apparently little more than a momentary diversion from the main action of Lucy’s reception of Frank Greystock’s fateful letter. An attentive reader of our own time might pause for a second in vague appreciation of the Lewis Carroll-like joke being played, but would be unlikely to proceed much further. Nevertheless, the distinction drawn here goes well beyond this exchange, informing the form and content of The Eustace Diamonds, and bearing directly on its articulation of the law, custom and force. At first glance, Nina is distinguishing between the say-able and the do-able: while hunchy may not technically be a part of the English Language, one may certainly take a knife to the bread and extract the desired bit. Yet ‘hunchy’ is a word – a word that, as Nina demonstrates, can possess an effective reality: it can designate in a way that permits both recognition and action. More precisely, then, Nina distinguishes between what is officially articulable (what is in the dictionary, and therefore counts as proper English), and what may be said and done beyond the realm of official sanction. Nina is perfectly content to let the dictionary stand guard over what counts as acceptable language, but refuses to let this function impede her ability to possess and consume the desired object. Nina’s distinction opens up a gulf that runs throughout this novel, between the realm of the sanctioned (whether in legal code that, like the dictionary, is supposed to provide linguistic-material force, or in the less explicit but no less potent realm of custom) and the pragmatic field of what characters can actually say and do, especially in pursuit of self-interest and acquisition. Although the most forceful illustrations of this gulf occur around the disruptive figure of Lizzie Eustace, the more amiable Lucy testifies to the gulf’s presence as well, and its effects can be felt throughout the social field of the novel.

Trollope imagines society in a state of transition, and thus the relation between the sanctioned and the pragmatic…must necessarily also be changing.

This gulf, between sanctioned behavior and the pragmatic field of force, might be otherwise figured, and in any event cannot be taken as static.1 I chose the metaphor of a gulf with reference to the way that those who bind themselves to the sanctioned side (like Lord Fawn, or the police) often find themselves stopped or frustrated at its boundary. One might also imagine the sanctioned as a region embedded in the larger plane of force, or the pragmatic as an excessive force destabilizing the ordered sphere of the sanctioned, etc.2 However one chooses to imagine the sanctioned and the pragmatic, it is clear from the text that Trollope imagines society in a state of transition, and thus the relation between the sanctioned and the pragmatic (both of which are necessarily embedded in the social) must necessarily also be changing.3 Likewise, the general terms “sanctioned” and “pragmatic” I use here have more particular historical meanings in Trollope’s novel. The pragmatic is connected to a particular version of liberal civil society (often imagined in conservative critiques thereof), defined by self-interest, tentative contractual relations and a dissolution of older social bonds. The sanctioned joins fields otherwise disconnected, taking in both common and positive aspects of law, as well as the compulsion of social custom. The Law in particular is imagined by figures like Camperdown as a force containing the excesses of the pragmatic actions of individuals. As figures like Lizzie make abundantly clear, the power of the law, like that of custom, is far from absolute and may be combated. The Eustace Diamonds is a novel filled with metaphorical, hypothetical and verbal combat – present even in the verbal sparring of Nina and Cecilia over their bit of bread. This combat is enabled by the gulf between the sanctioned and the pragmatic, but is also part and parcel of the latter field.

It would certainly be breaking no new critical ground to insist that Trollope draws our attention to the self-interested behavior of individuals in Victorian society, or that he was interested in the law and politics. Legal issues in Trollope’s novels have been taken up by some of his earliest critics and the law in Trollope seems to be a topic of renewed interest in Victorian literary studies.4 Likewise, Trollope’s self-designation as an “advanced, but still conservative Liberal” has been creating headaches ever since he wrote it, and critical opinion has affixed a wide range of political positions to the novelist and one-time political hopeful.5 Even Trollope’s depiction of the self-interested behavior of various characters invites a variety of interpretations. We might read many of Trollope’s novels in terms of an implicit conservative critique – blatantly self-interested parvenus (Lizzie, Melmotte, etc.) standing against respectable figures tied to landed estates (Camperdown, Roger Carbury, etc.) and serving as a sign of declining times. By contrast, D.A. Miller reads Trollope as both complacent about and complicit with his consumption-obsessed society, the reading of his serial novels reenacting the behavior of his novels’ characters, “who uninhibitedly desire what Trollope calls, in one of his favorite legitimating phrases, ‘the good things of the world’” (111). Lauren M. E. Goodlad offers an alternative to both of these perspectives, reading Lizzie’s “hyper-romantic acquisitiveness” as a structural parody of “imperialism run amok,” as typified by Disraeli (“Geopolitical Aesthetic” 871). By Goodlad’s reading, what is most important in The Eustace Diamonds is not Trollope’s quasi-conservative commitment to gradualism (aligned with his liberal anxiety), but his embodied critique of an Imperialist politics and aesthetics. More generally, Goodlad argues that Trollope’s realism should not be confused with a complacent confirmation of things as they are, but rather attempts sociological fidelity and engages in formal experiments to capture political realities of his day. “Realism of this kind, neither naïve nor self-naturalizing, aspires to that historical grasp that defines the geopolitical aesthetic at work” (“The Great Parliamentary Bore” 116). While Miller alerts us to a dimension of Trollope’s work we would do well to keep in mind, I suspect we may have more on the whole to gain from Goodlad’s desire to find tools for analysis and critique within the form and content of Trollope’s novels.

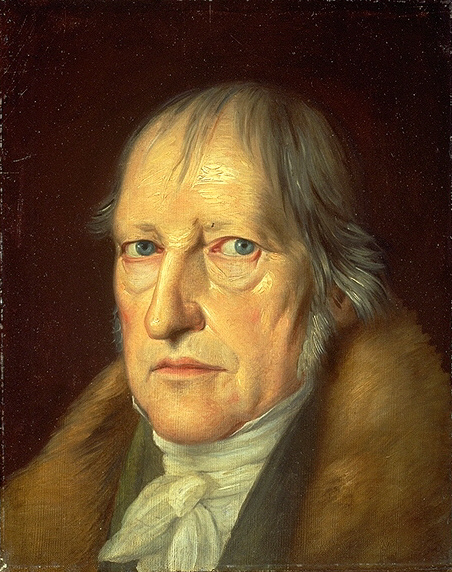

ALTHOUGH THIS PAPER does not follow Goodlad’s concern with imperialism per se, it does seek to unearth the novel’s sensitive analysis of political discourse as embodied in its characters and expressed in its form. This analysis varies between critique and description, too conscious of danger to lapse into complacent reporting but on the whole less didactic than the narrator’s attacks on Lizzie might lead us to think. Besides Goodlad, my account of the pragmatic-sanctioned gulf and its combats in Trollope’s novel also draws on critical work done by Ayelet Ben-Yishai and Frederik Van Dam. Although unlike Ben-Yishai I join common law and positive law as two different but related means of producing social sanction, I follow her in focusing on questions of gossip and propriety in relation to social power in this novel. I follow Van Dam in relating law to violence in this novel and reading Trollope with the help of German philosophy, but read Lizzie in terms of civil society (not natural law) and take Hegel, rather than Benjamin, for my point of reference. Although we have little reason to believe Trollope read significantly in German philosophy, he likely encountered elements of Hegel’s political philosophy, as mediated through Carlyle’s writings. In particular, Trollope would have encountered a vision of liberal civil society as structurally organized around the conflict of private interests. This vision appears throughout the text of the Eustace diamonds, in matters of personal affection as well as property and public status, usually in metaphorically elevated language: a legal argument over jewels becoming a combat of Greeks and Romans, for instance. Trollope’s presentation of this conflict registers what he seems to regard as genuinely troubling aspects of English civil society, while effectively counteracting some of Carlyle’s more apocalyptic expectations. In moderating Carlyle’s social prophesy while maintaining elements of his social vision, Trollope more closely resembles Hegel, who took liberal civil society to be a necessary development, however troubling its effects.

ALTHOUGH THIS PAPER does not follow Goodlad’s concern with imperialism per se, it does seek to unearth the novel’s sensitive analysis of political discourse as embodied in its characters and expressed in its form. This analysis varies between critique and description, too conscious of danger to lapse into complacent reporting but on the whole less didactic than the narrator’s attacks on Lizzie might lead us to think. Besides Goodlad, my account of the pragmatic-sanctioned gulf and its combats in Trollope’s novel also draws on critical work done by Ayelet Ben-Yishai and Frederik Van Dam. Although unlike Ben-Yishai I join common law and positive law as two different but related means of producing social sanction, I follow her in focusing on questions of gossip and propriety in relation to social power in this novel. I follow Van Dam in relating law to violence in this novel and reading Trollope with the help of German philosophy, but read Lizzie in terms of civil society (not natural law) and take Hegel, rather than Benjamin, for my point of reference. Although we have little reason to believe Trollope read significantly in German philosophy, he likely encountered elements of Hegel’s political philosophy, as mediated through Carlyle’s writings. In particular, Trollope would have encountered a vision of liberal civil society as structurally organized around the conflict of private interests. This vision appears throughout the text of the Eustace diamonds, in matters of personal affection as well as property and public status, usually in metaphorically elevated language: a legal argument over jewels becoming a combat of Greeks and Romans, for instance. Trollope’s presentation of this conflict registers what he seems to regard as genuinely troubling aspects of English civil society, while effectively counteracting some of Carlyle’s more apocalyptic expectations. In moderating Carlyle’s social prophesy while maintaining elements of his social vision, Trollope more closely resembles Hegel, who took liberal civil society to be a necessary development, however troubling its effects.

As Nina understands her prerogative to possess a desired bit of bread to override abstract concerns of linguistic correctness, Hegel takes will-based possession, or “the absolute right of appropriation which human beings have over all ‘things’” to be the subject’s first substantial right (60). In opposition to the purely negative freedom of abstract personality, the right to possession provides a concrete actualization of freedom, realizing the difference between the subject, who has ends and rights, and the object, which has neither in itself. From this material base, Hegel moves on to contracts (whereby possession is affirmed by other subjects and a larger community), morality (returning to the individual) and ethical life (Sittlichkeit, returning to the community) – the last section encompassing the family, Civil Society (die bürgerliche Gesellschaft) and the State. Civil Society exists between the private sphere of the family and the public stage of the State, a system of interdependence arising from the coordinated attainment of private ends. As citizens (Bürger) simply pursue private interests, civil society begets a situation in which

Particularity by itself [für sich], given free rein in every direction to satisfy its needs, contingent caprices, and subjective desires, destroys itself and its substantial concept in this process of gratification. At the same time, the satisfaction of need, necessary and contingent alike, is contingent because it arouses [new desires] without end, [and] is in thoroughgoing dependence on arbitrariness and external contingency … In these contrasts and their complexity, civil society affords a spectacle of extravagance as well as want and of the physical and ethical degeneration common to them both. (182)

Civil society, resting on a fundamentally contingent basis (individuals pursuing private ends), structurally tends towards instability and inequality. This condition is further exacerbated by the differences in skills and resources with which members enter into civil society – and, in connection with this, Hegel characterizes civil society as inherently tending towards class conflict. Perhaps Hegel’s most famous characterization of civil society is as a field of universal violence or conflict: “civil society is a battlefield of individual private interest, [a battlefield of] all against all.”6 This formulation translates the personal and physical violence of Hobbes’s bellum omnium contra omnes into the mediated violence of conflicting material interests, with a retained possibility of physical violence. For Hegel, both forms of violence are contained by the State, but this containment is a necessarily partial procedure. Nevertheless, for Hegel’s civil society, as in Trollope’s novels, most combat occurs in social, cultural, political and legal fields.

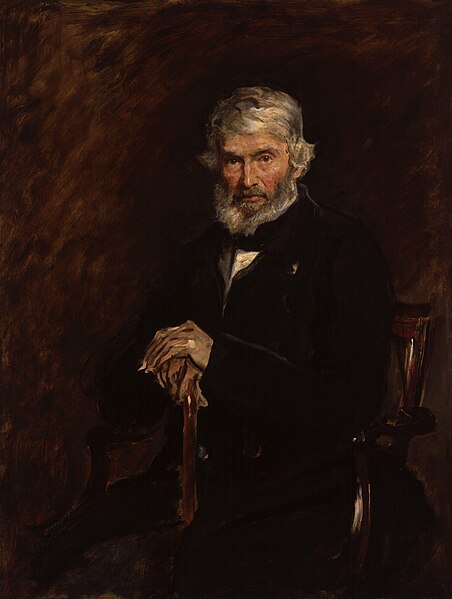

Carlyle borrowed directly from Hegel in his Heroes and Hero Worship, and shared with Hegel the more general Romantic Post-Kantian project of repairing the ravages of objectifying rationality, a rationality manifest both in political violence and cultural alienation. For both thinkers, liberal civil society was a feature of a more general drive to rationalization, and entailed the destruction of older forms of social relations and organization. Carlyle connects “The Law of the Stronger, law of Supply-and-demand, law of Laissez-faire, and other Laws and Un-laws” (24) – thus effectively equating the unregulated pursuit of individual self-interest (Laissez-faire) with the development of conflict-inducing inequalities (the law of the Stronger). Like Hegel, Carlyle connects Laissez-faire liberal society with the excessive growth of particular gratification: “Laissez-faire, Supply-and-demand … Leave all to egoism, to ravenous greed of money, of pleasure, of applause” (185). Carlyle similarly takes up as mutually implicit calls for “Laissez-faire, and Every man for himself” (208). Both thinkers read liberal or civil society, the society governed by the pursuit of individual economic self-interest, as structurally tending towards universal conflict and violence. Violence and conflict are not contingent occurrences under the regime of civil society (resultant from a particular culture or historical circumstances), but are rather woven into the fabric of the very system. Whether we read Carlyle as a neo-Feudalist, a worshippers of heroes, an often-confused socialist, or any of a number of other figures, it is clear that he thought a society constituted around the non-law of Laissez-Faire could not endure, but must instead be reconstituted.

AS ANYONE FAMILIAR with The Warden’s Dr. Pessimist Anticant might tell you, Trollope was perfectly happy to mock Carlyle’s heavy-handed prophesying. As N. John Hall notes, “When writing for the public Trollope’s policy was to pay Carlyle flattering compliments and then say he was all wrong” (203). Hall is certainly right to read Trollope as conflicted about Carlyle, being “both immensely awed and impressed, and repeatedly annoyed and troubled” (205). Hall also notes, however, that several of Trollope’s writings appear to advocate for views which are basically moderated – or less pessimistic and therefore less drastic – “Carlylism.” Hall cites a letter in which Trollope lambasts Carlyle’s Latter Day Pamphlets, but neglects the line from the same letter in which Trollope declares that he “used to swear by some of [Carlyle’s] earlier works” (Letters 29). As Ruth ApRoberts notes, there is also a good chance that Trollope exaggerates his distaste, as he is in the process of imitating and modifying Carlyle in his own The New Zealander (214).7 ApRoberts goes on to indicate places where Trollope modifies Carlyle and to outline a significant difference between the two figures on the point of aesthetics. If we can take the readings of two critics as a sufficient consensus (together with Wilson B. Gragg’s more cursory 1958 note), then it seems reasonable to infer that Trollope was strongly influenced by Carlyle, impressed by but desiring to moderate him politically and likely resisting him in the field of literary aesthetics, particularly regarding Carlyle’s low opinion of the powers of the realistic novel.

AS ANYONE FAMILIAR with The Warden’s Dr. Pessimist Anticant might tell you, Trollope was perfectly happy to mock Carlyle’s heavy-handed prophesying. As N. John Hall notes, “When writing for the public Trollope’s policy was to pay Carlyle flattering compliments and then say he was all wrong” (203). Hall is certainly right to read Trollope as conflicted about Carlyle, being “both immensely awed and impressed, and repeatedly annoyed and troubled” (205). Hall also notes, however, that several of Trollope’s writings appear to advocate for views which are basically moderated – or less pessimistic and therefore less drastic – “Carlylism.” Hall cites a letter in which Trollope lambasts Carlyle’s Latter Day Pamphlets, but neglects the line from the same letter in which Trollope declares that he “used to swear by some of [Carlyle’s] earlier works” (Letters 29). As Ruth ApRoberts notes, there is also a good chance that Trollope exaggerates his distaste, as he is in the process of imitating and modifying Carlyle in his own The New Zealander (214).7 ApRoberts goes on to indicate places where Trollope modifies Carlyle and to outline a significant difference between the two figures on the point of aesthetics. If we can take the readings of two critics as a sufficient consensus (together with Wilson B. Gragg’s more cursory 1958 note), then it seems reasonable to infer that Trollope was strongly influenced by Carlyle, impressed by but desiring to moderate him politically and likely resisting him in the field of literary aesthetics, particularly regarding Carlyle’s low opinion of the powers of the realistic novel.

For a novel in which physical violence seems to be absent, The Eustace Diamonds is remarkably full of violent language. In just the first few chapters, Lizzie has opened a military “campaign,” Camperdown intends to “jump upon” Lizzie, her aunt engages in a devastating “combat” with Lizzie, and even the usually reserved Lucy is imagined as “fighting, if it were necessary, down to the stumps of her nails.” (14, 32, 44, 52) “Attacks” frequently figure in the social interactions of characters, while “fighting” seems to characterize both such interactions and the default condition of men like Frank and Lord Fawn trying to make their way in the world (even as Fawn consistently seeks to flee a “scrape”). Violent language inhabits the edges of this text no less than its center: Nina imagines that, like Lucy, she would “fly at” anyone who insulted her lover, and Lizzie can complacently respond to Frank’s objection to staying at Portray that he “has a man there in the Cottage with me who would cut his throat in his solitude” “Let him cut his throat” – this latter quote perhaps reinforcing the reader’s sympathy with Herriot’s reticence to talking with Lizzie (212, 181-2). Even as refined a character as Lady Glencora is imagined to “take up the cudgels” for Lizzie against Fawn (435). As Hegel takes a universal combat to be the defining feature of civil society, waged on the battlefield of private interest, Trollope’s novel imagines individual melees and larger war as constant presences on the level of metaphor, standing in for very real conflicts over material possessions and social power.

When Lady Fawn concludes her letter to Lucy informing her of Frank’s likely infidelity by invoking “the mercy of God” it comes as a bit of a shock to the reader (584) – what, after all, could divine mercy have to do with the violent field of material and matrimonial conflict on which Lucy has been injured? Although God has appeared before, it is usually in well-worn formulas (Thank God, God knows, etc.). There has, however, been a different sort of divine presence running through the novel. Raging against Lord Fawn’s threat to withdraw his offer of marriage, Lizzie “was stamping her little feet, and clenching her little hands, and swearing to herself by all her gods, that this wretched, timid lordling should not get out of her net” (82). Likewise, the narrator imagines the meager wants of poor Macnulty thus: “To have her meals, and her daily walk, and her fill of novels, and to be left alone, was all that she asked of the gods” (174). The gods thus invoked seemed to fall somewhere between household gods and a full-blown pagan pantheon – serving as a source to appeal to for refuge for Macnulty, while appearing as far more warlike beings to be appeased by Lizzie. Their longest invocation comes when Frank responds to Lizzie’s accusation that he seeks repose in Lucy:

“We seldom know what we want, I fancy. We take what the gods send us.” Frank’s words were perhaps more true than wise. At the present moment the gods had clearly sent Lizzie Eustace to him, and unless he could call up some increased strength of his own, quite independent of the gods, – or of what we may perhaps call chance, – he would have to put up with the article sent. (207)

As Hegel insists that civil society is necessarily shot through with contingency (being rooted in a disparate mass of desires and governed only by the pursuit of subjective interests), Trollope’s battlefield of individuals seeking meals, victory and the indefinite end of self-interest is ruled over by gods of chance. Although an individual may summon strength to resist the apparent trajectory of a given godsend (a term which appears elsewhere in the text), there is nonetheless the sense that the gods of chance constitute the field on which both resistance and passive acceptance take place.8 Furthermore, the fact that Frank does, after quite some time, find strength to resist Lizzie seems less due to personal resolve than the gradual work of guilt regarding Lucy in combination with the shock at seeing a travel-worn Lizzie.9 While the narrator may (slightly ironically) dub Frank a “hero,” it is difficult to see where exactly he differs from the mass of “Greeks and Romans” he imagines fighting over the “fair Helen” of Lizzie’s diamonds, or the pack of “myrmidons” Lizzie worries Mr. Camperdown might send for the same booty (246, 37).

Indeed, if Frank is distinguished from the masses of self-interested individuals on the faux-heroic field of battle for economic advantage and social prestige, such distinction seems to lie less in himself than in his ultimate object-choice, Lucy. While all the world may be a battlefield of egoism, Lucy appears as a model of charitable concern with others, without any particular interest in material possessions. Despite such admirable qualities, Lucy is nonetheless “inescapably embedded in the very ‘real’ situation of the marriage economy,” in which she engages in her own sort of battle to maintain her connection to Frank and avoid appropriation by the Fawn family (Goodlad 105-7). To Goodlad’s example of Lucy’s loss of Frank being likened to the loss of a limb, we may add an image of Lucy taking on a role like that of Frank’s Greeks and Romans:

Poor Lucy received the wound which was intended for her. The enemy’s weapons had repeatedly struck her, but hitherto they had alighted on the strong shield of her faith. But let a shield be never so strong, it may at last be battered out of all form and service. On Lucy’s shield there had been much of such batterings, and the blows which had come from him in whom she most trusted had not been the lightest. (458-9)

This battle-exhausted Lucy stands in marked contrast to the fierce combatant for Frank’s good name who manages to send a frightened Lord Fawn “off to the house as quick as his legs could carry him” (215). Lucy’s combativeness is not identical with Lizzie’s acquisitive fierceness, being mediated through a male figure: she will fight “down to the stumps of her nails,” but this fight must be justified by a lover’s (or husband’s) “interests” (52). If secure in such a figure, Lucy will pursue his (and her) interests even against the tide of social custom, accusing her employer’s son and a peer in parliament of voicing untruths. The Governess must be informed by her very pupils “that under no circumstances could a lady be justified in telling a gentleman that he had spoken an untruth” – a truth she concedes when considered abstractly, reinforced by the social inequality of Lucy and Lord Fawn (214). Nevertheless, in the actual situation of their confrontation, Lucy is unable to ignore the injury she believes Lord Fawn to have inflicted upon her, concluding in a pitched (if usually respectful) battle against the whole Fawn family.

UNLIKE LUCY’S ALMOST unintentional but determined battle with Fawn interests, Lizzie offers a mix of different kinds of battle: planned and spontaneous combats, feints and frontal charges, bold sallies and frightened retreats. At the beginning of the novel, Lizzie seems not entirely ready for the fights that await her. Although she manages to evade “any further attack” by a well-timed escape from the unprepared Camperdown, she also shows a failing courage in her conflict with Lady Linlithgow, nearly overcome by the “stress of combat” (34, 47). She suffers in large part from a lack of familiarity with the terrain of the battlefield to which her sudden wealth has elevated her: “Though she was clever, sharp, and greedy, she had no idea what her money would do, and what it would not; and there was no one whom she would trust to tell her.” (13) Moreover, “she was, and felt herself to be absolutely, alarmingly ignorant, not only of the laws, but of custom” in matters of inheritance (37). Often given to flight in the face of strength, or its possibility in the vague unknown, Lizzie is quite prepared to exert a cruel violence once a weak foe is scented. Contemplating revenge on Lord Fawn, Lizzie insists that his punishment should be “That he should be beaten within an inch of his life; – and if the inch were not there, I should not complain,” overruling Frank’s objection with the declaration “I think I could almost do it myself.” Simultaneously raising her hand “as though there were some weapon in it” (186).

Having resisted Lizzie’s appeals to inflict various forms of violence on Lord Fawn, Frank finally declares,

Let us understand each other, Lizzie. I will not fight him, – that is, with pistols; nor will I attempt to thrash him. It would be useless to argue whether public opinion is right or wrong; but public opinion is now so much opposed to that kind of thing, that it is out of the question. I should injure your position and destroy my own. (186)

A humorous counterpoint to Lizzie’s exaggerated passion, Frank’s objection also reminds us of the very real constraints on violence in the society which he and Lizzie inhabit. While the force of the police awaits those who step too far from the bounds of social sanction (Frank notes that the police, unlike him, may seize persons by the throat), the more immediate and pervasive force of custom and public opinion is usually enough to keep politicians like Frank and even newly minted society ladies like Lizzie in order. While the capacity to thrash Fawn probably exists within Frank’s bare physical force, his awareness of social expectations effectively erases this from his field of conceivable action (however interested he may be by Lizzie’s romances). While Lizzie may display a theatrical indifference to material concerns and social position – threatening to cast her diamonds into the sea or imagining absconding with her corsair – her actions reveal her to be at times almost hysterically (in Trollope’s language) averse to the danger of losing social status or material advantage. As Ben-Yishai (against William Kendrick) contends that Lizzie “actually learns a great deal” about the law (107 n.24), we might read this novel as a gradual education of Lizzie on matters of both law and custom, discovering new limitations but also new powers in her social sphere. While such education likely reveals its limits in some of Lizzie’s actions both early and late in the novel, her brief achievement of great social success with the aid of Lady Glencora should not be overlooked as a sign of her successful negotiation of these limitations and powers.

The same sphere of public opinion that Frank fears and Lizzie learns (somewhat) to negotiate appears in this novel as the great antagonist of the hapless Lord Fawn. Having engaged and then conditionally attempted to disengage himself from Lizzie, Lord Fawn feels acutely the gaze of “The Eye of the Public” (as chapter sixty seven has it). Fawn is driven to Lizzie in the first place when, “conscious of having been subjected to hardship by Fortune,” he “looks to marriage as an assistance in the dreary fight” of making his way as a poor Lord and politician (65). After attempting to break off his engagement from Lizzie with reference to the potentially scandalous problem of the Eustace Diamonds, Fawn finds himself at a confused loss of what to do once rumors of his action begin to circulate widely. Though perpetually desirous of appearing unimpeachable before the public, Lord Fawn is incapable of following its shifting tides. Moreover, he finds himself more immediately caught in a war in which he seems to have little say. The Hittaways and Fawn court set themselves firmly against any match with Lizzie, as “various stratagems were to be used, and terrible engines of war were to be brought up, if necessary, to prevent an alliance which was now thought to be disreputable” (137). Lady Glencora, on the other hand, has determined to take Lizzie’s side – and as she is the wife of the leader of Lord Fawn’s party, this is no meager ally for Lizzie. Glencora appears conscious that her position effectively removes her from some of the social constraints under which Lord Fawn suffers. Seeking to rebuke her ladyship’s too-personal inquiry, Fawn’s “My private affairs to do seem to be uncommonly interesting” does nothing to hinder Glencora, “whom nothing could abash” (525). Public opinion, and the custom connected to it, not only change over time but also can also apply differently to different subjects depending on their social standing. As Frank indicates that it is useless to argue whether public opinion were right or wrong, Likewise Glencora’s opinions take on a social force independent of their veracity or falsity.10

If Lady Glencora is able to evade some of the commands of polite custom by virtue of her position at the center of polite society, Mrs. Carbuncle provides us with a testing of custom’s limits from a fairly different position. Seeking to gather as much wealth for the marriage of her (nominal) niece as possible, she launches a “spirited attack” on a Mrs. Hansbury Smith. Unsatisfied with a small offering from a mostly-lapsed acquaintance, Carbuncle appeals to an invented system of reciprocity under which a niece may stand for a daughter, adding that “I think that this is quite understood now among people in society.” The reply comes that, although the lady (writing under the direction of her husband) “quite acknowledge[s] the reciprocity system,” (s)he cannot acknowledge such an expansion of its claims to have taken place. Like Glencora, Carbuncle appears incapable of being abashed, but her cause is less an unimpeachable social position than a vulgar frankness about economic self-interest: “People have come to understand that a spade is a spade, and £10, £10,” (514). While the Hanbury-Smith reply indicates that the world does not work exactly as her statements about people’s understandings would indicate, “in her set, it was generally thought she did quite right” (515). Moreover, the fact that Hanbury-Smith nonetheless acknowledges “the reciprocity system” suggests that (s)he understands and acknowledges the operation of self-interest just as well as Mrs. Carbuncle – merely that they differ as to a detail of its specific demands.

If Mrs. Carbuncle is indeed correct in reading her actions as typical of a rising, soon-to-be-dominant social order, then it might seem that we would be justified in joining old Lady Fawn’s lamentation at the “theory of life and system on which social matters should be managed, as displayed by her married daughter.” The Hittaways, like Lizzie, are characterized by the narrator as skilled players of social-economic games, and Mrs. Hittaway is unsparing of her old-fashioned mother. Lady Fawn is told “that under the new order of things promises from gentlemen were not to be looked upon as binding, that love was to go for nothing, that girls were to be made contented by being told that when one lover was lost another could be found.” Lady Fawn finds such dire prophecies confirmed by both her own experience and her neighbors, who inform her that “that the English manners, and English principles, and English society were all going to destruction in consequence of the so-called liberality of the age.” (470). Lady Fawn, like Trollope, is a Liberal, but finds herself no less alarmed by the “liberal” allowances her age seems to make for people’s behaviors. Liberalism was often imagined by its critics (including Carlyle) as an epoch in which relatively weak contracts came to replace the more hale organic social bonds of earlier eras. Lady Fawn’s concern with Gentlemen’s lax attitudes towards promises provides an amatory compliment to this socio-economic critique. Mrs. Hittaway’s field of marital competition reenacts precisely the features of Laissez-Faire liberalism Carlyle inveighed against, taking a zero-sum approach to resource allocation and governed by no principle save individual self-interest.

If Lady Fawn comes to a despairing acceptance of the new order, Mr. Camperdown is far less resigned to the incursion of the same as embodied in Lizzie’s attempts to appropriate the Eustace Diamonds. Initially content to proceed through polite channels to seek the restoration of the family jewels, Camperdown quickly learns that letters, even letters threatening legal action, wield little power over someone who, deciding to neglect polite custom, simply declines to respond. Apparently resolving to take his own liberties with polite custom, Camperdown confronts Lizzie in her own carriage, frightening her but failing to achieve his end. While Lizzie’s image of Camperdown’s myrmidons coming to take her jewels never quite comes to pass, one is not sure that Camperdown would not resort to such measures had he the legal warrant to do so. Mr. Camperdown, like Andy Gowran, identifies himself with the interests of the Eustace estate, and the Law for him is supposed to provide for the defense of landed estates and their respectable patrons: “It was, to Mr. Camperdown’s mind, a thing quite terrible that, in a country which boasts of its laws and of the execution of its laws, such an impostor as was this widow should be able to lay her dirty, grasping fingers on so great an amount of property, and that there should be no means of punishing her” (217). Where basic social decency (or social custom) fails to restrain the actions of the vulgar and self-interested, the Law must exert its force. Unable ultimately to bring this force to bear, Camperdown rages against Lizzie, hurling a mass of epithets at her (harpy, swindler, thief, etc.) and fantasizing about legal punishment inflicted on her, asserting, for instance, “that she ought to be dragged up to London by cart ropes” (616).

MR. DOVE DRAWS our attention to a mild hypocrisy in Mr. Camperdown’s thought: while Camperdown rages against Lizzie’s acquisitiveness, he nonetheless attempts to use the law to the end of material advantage. For Camperdown, this material pursuit is paradoxically justified by the great amount of money at stake: “The magnitude of the larceny almost ennobled the otherwise mean duty of catching the thief” (221). Dove refuses to permit such a paradox, questioning whether “the Law [would] do a service … if it lent its authority to the special preservation in special hands of trinkets only to be used for vanity and ornament” (223). Dove’s conception of the Law, as several critics have noted, is unapologetically Romantic. In Dove’s words, “the Law, which, in general, concerns itself with our property or lives and our liberties, has in [the matter of heirlooms] bowed gracefully to the spirit of chivalry and has lent its aid to romance; – but it certainly did not do so to enable the discordant heirs of a rich man to settle a simple dirty question of money” (223-4). As Ben-Yishai notes, this paradoxically aligns the respectable Dove and the hyper-romantic but shameless Lizzie (110-1). Moreover, in removing the law from “dirty” questions of money, Dove effectively reduces the Law’s capacity to regulate the self-interested behavior of individuals. Mr. Dove’s faith in the Law, taken to its logical extreme, resembles Trollope’s characterization of the High Conservative as an “advanced Buddhist,” “possessing a religious creed which is altogether dark and mysterious to the outer world,” and being similarly unconcerned with acting in that outer world (29-30.)11

To Lizzie’s distress, the police in this novel are neither Romantics nor advanced Buddhists, being perfectly happy pursue dirty questions of money. The police and their attendant system of justice and punishment are some time in coming in this novel, being anticipated by the fears of Lizzie, the hopes of Camperdown and the admonitions of Lady Linlithgow and Lady Fawn. Linthgow hurls threats of “Theft, and prison, and juries, and judges” at Lizzie’s head, while Lady Fawn responds to Lucy’s objection that she could not be patient in the face of Fawn’s insults, “That is what wicked people say when they commit murder, and then they are hung for it” (48, 213). Both of these statements evince a social awareness of the kind of violence Van Dam reads as structurally inherent in positive law (which permits retroactive self-justification), but likewise being a feature of law more generally.12 For all the violent power they are supposed to have, however, the police find themselves curiously incapable of preventing Lizzie’s self-interested and illegal (as we know from the narrator) activity. This incapacity is partially attributed to institutional features, including a possibly counter-productive commitment to secrecy. But they also find themselves bound by the sanction of social custom. “Had it been an affair simply of thieves, such as thieves ordinarily are, everything would have been discovered long since; – but when lords and ladies with titles come to be mixed up with such an affair, – folk in whose house a policeman can’t have his will at searching and brow-beating, – how is a detective to detect anything?” (445) Forced to observe the private rights and social niceties of the upper classes, the police cannot produce their usual results and exert their accustomed force on the behavior of individuals. The police are also thrown off by a more subtle form of social custom, in a customary form of thinking: even the ingenious Gager cannot quite sort out the facts of the theft initially, being incapable of keeping “his mind clear from the alluring conviction that a lord had been the chief of the thieves” (450).

At least since Walter Kendrick’s 1979 article, critics have recognized a troubling tension in Trollope’s attempt to bring closure to The Eustace Diamonds. Frank’s decision to return to Lucy, and Lizzie’s abandonment to Mr. Emilius seem to reinforce the narrator’s moral priorities. For Kendrick, the elevation of the true Lucy over the false Lizzie is at odds with his larger project of “corrective” realism: “the paradox of Trollope’s realism is that it lives on the energy of what it condemns” (156). For Ben-Yishai, the narrator’s desire to impose and fix an absolute truth is at odds “the more open, retalivistic” mode of communal truth-making “of the novel itself” (118). For Goodlad, “Trollope’s narrator struggles unsuccessfully to control the novel’s experiment in anti-realist characterization” in Lizzie’s hyper-romanticism (872). Albert Pionke takes a somewhat different approach, reading The Eustace Diamonds as part of a larger attack on the law, resisting tendencies towards romanticism in the law, Lizzie, and fiction more generally, while staking out a superior claim to truth via its unflinching realism. In different ways, each of these approaches assumes an enmity between Trollope or his narrator and Lizzie – an entirely reasonable inference, given that the narrator aligns himself with Lizzie’s enemies at the beginning of the narrative and seems at times as eager as Camperdown to make us aware of her base motives and actions. And yet the narrator does not exactly declare himself Lizzie’s enemy, confessing only that he does not love her (1). Frank and Lucy certainly seem to figure an idealized reconciliation between Frank’s active ambition and Lucy’s truthful altruism over and above the world of Carbuncles and Emiliuses. At the same time, I am not sure that the narrator who approvingly notes that we dine and sympathize with villains (or those who would be villains by the standards of romantic fiction) means us to feel no sympathy whatsoever for Lizzie. The concluding notes of the novel seem mostly interested in invoking interest in its unheroic heroine, playfully soliciting the reader’s prediction of Lizzie’s future happiness in its final lines and promising “that the future fate of this lady shall not be left altogether in obscurity” in its penultimate chapter.

Like Hegel, Trollope does not seem to imagine that there is any going back on the project of civil society, and this sense informs both the content and the aims of the Eustace Diamonds. The quasi-feudal world of Gowrans and Camperdowns is a remnant attesting to uneven development, not a viable alternative to the realities of the present. As Goodlad and Andrew Miller aptly demonstrate, even Lucy’s tremendous loyalty will not extend to permitting herself to become an heirloom of the Fawn estate. For Hegel, the State cannot destroy the contingent and violent character of civil society, but must aim to limit its excesses without succumbing to the perfectionist fantasy that entails eliminating particularity. Neither the State apparatus of Law nor the social force of custom are ultimately able to prevent Lizzie from realizing the spoils of an act that “she knew well enough” to be wrong (48).13 Yet it is not at all clear that the world governed by Camperdown would be a pleasant, or even a more just place. Despite the narrator’s insistence that Lizzie is perfectly well acquainted with right and wrong, it also hardly evident in this novel that the sanction-producing branches of society, whether legal or customary, are any more fundamentally inclined to produce results in line with furthering the right and repressing the wrong. Despite being occasionally overwhelmed in combat, Lizzie is at times able to wield a daring inaccessible to the properly cowardly Lord Fawn. Moreover, by the end of this novel, she has attained an almost admirable notion of how to exploit gaps in the processes of the law (her social reputation likely having become unsalvageable). In a society in which the borders between the sanctioned and the pragmatic are inherently unstable, even the narrator must concede that Lizzie is capable of playing “her game well” (8), and she certainly makes for an interesting warrior to follow.

THE INTEREST WE take in Lizzie is not something we can entirely extract from either a vaguely sympathetic curiosity or a schadenfreudliche sadism (assuming we follow the old Duke in gleefully anticipating bad times approaching for her), neither of which are guaranteed to avoid an attitude of complacent entertainment. Trollope neither claims nor desires to present us with a revolutionary text, preferring instead a mode of realism that aims to strike a delicate balance: “The true picture of life as it is, if it could be adequately painted, would show men what they are, and how they might rise, not, indeed, to perfection, but one step first, and then another, on the ladder” (276). Although Trollope seems at times to oppose a narrated realism (or realistic anti-realism) to a narratorial moral certitude, I suspect this may not be the only means of bridging the is and the ought, as imagined in Trollope’s literary project. Such a didactic mode would, after all, be tantamount to the forceful exercises of the law and custom Trollope has just demanded that we notice repeatedly fail – and Mrs. Carbuncle is certainly happy to remind us of the dangers of taking allegedly common or assumed knowledge (an unquestioned right) as a moral compass. What if a sensitive inhabitation of the discourses and shifting structures that circulate through, constitute and reconstitute society, practiced in accord with a disciplined awareness of both the powers and limitations of literary form, were enough to generate a sense of uneasy entertainment in the reader? Although this may be an illusory dream of realism, I am not sure that we are well served by a too hard and fast line drawn between pleasurable entertainment and critical awareness. I suspect that we are capacious enough to laugh at Lizzie, Lord Fawn and Miss Macnulty even while registering the different positions with which the gods of chance have presented them and the according differentials of power and combat between them (and perhaps differently inflecting that laughter). Likewise, I imagine we are entirely capable of laughing Nina and Cecilia’s unintentional joke while appreciating and analyzing the troubling and suggestive implications of its distinction.

♦

Andrew R. Lallier is a graduate student at the University of Knoxville. This essay is the winner of the 2013 Trollope Prize (graduate competition).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ApRoberts, Ruth. “Carlyle and Trollope.” Carlyle and his Contemporaries. Ed. John Clubbe. Durham: Duke University Press, 1976. 205-226. Print.

_____________. “Trollope and the Zeitgeist.” Nineteenth-Century Fiction 37 (1982): 259-271. Print.

Ben-Yishai, Ayelet. “The Fact of a Rumor: Anthony Trollope’s The Eustace Diamonds.” Nineteenth-Century Literature 62.1 (June 2007): 88-120. Print.

Carlyle, Thomas. Past and Present. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005. Print.

Felber, Lynette. “The Advanced Conservative Liberal: Victorian Liberalism and the Aesthetics of Anthony Trollope’s Palliser Novels.” Modern Philology 107.3 (Feb 2010): 421-446. Print.

FisiChelli, Glynn-Ellen. “The Language of Law and Love: Anthony Trollope’s Orley Farm.” ELH 61 (1994): 635-653

Goodlad, Lauren M.E. “Anthony Trollope’s The Eustace Diamonds and ‘The Great Parliamentary Bore’”. The Politics of Gender in Anthony Trollope’s Novels: New Readings for the Twenty-First Century. Eds. Regenia Gagnier, Margaret Markwick and Deborah Morse. London: Ashgate, 2009. 99-116. Print.

_____________. “The Trollopian Geopolitical Aesthetic.” Literature Compass 7.9 (2010): 867-875. Web.

Hall, N. John. “Trollope and Carlyle.” Nineteenth-Century Fiction 27.2 (Sept 1972): 197-205. Print.

Hegel, G.W.F. Outlines of the Philosophy of Right. Trans. T.M. Knox. Ed. Stephen Houlgate. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008. Print.

Kendrick, Walter M. “The Eustace Diamonds: The Truth of Trollope’s Fiction.” ELH 46.1 (Spring 1979): 136-157. Print.

Miller, Andrew H. Novels Behind Glass: Commodity Culture and Victorian Narrative. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995. Print.

Miller, D.A. The Novel and the Police. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988. Print.

McMaster, R.D. Trollope and the Law. Houndmills: MacMillan Press Ltd, 1984. Print.

Pionke, Albert D. “Navigating ‘those terrible meshes of the Law’: Legal Realism in Anthony Trollope’s Orley Farm and The Eustace Diamonds” ELH 77.1 (Spring 2010): 129-157. Print.

Psomiades, Kathy Alexis. “Heterosexual Exchange and Other Victorian Fictions: The Eustace Diamonds and Victorian Anthropology.” Novel: A Forum on Fiction 33.1 (Fall 1999): 93-118. Print.

Taylor, Jenny Bourne. “Bastards to Time: Legitimacy as Legal Fiction in Trollope’s Novels of the 1870s.” The Politics of Gender in Anthony Trollope’s Novels: New Readings for the Twenty-First Century, eds. Gagnier et al, London: Ashgate, 2009: 45-60. Print.

Trollope, Anthony. The Eustace Diamonds. London: Chapman and Hall, 1876. Print.

Van Dam, Frederik. “Victorian Instincts: Anthony Trollope and the Philosophy of Law.” Literature Compass 9.11 (2012): 801-812. Web.

NOTES

- “pragmatic” as I use the term in this paper refers to relations of power and the self-interested action of individuals, not the more general (and more optimistically experimental) senses of the term employed by figures like William James and Gilles Deleuze. ↩

- I doubt that any simple figuration would be perfect on this count. While the gulf might engender the illusion that the sanctioned and the pragmatic were wholly separated, force/sphere would incorrectly suggest that the pragmatic lacked an order of its own, and region/plane might give the pragmatic a false claim to universality. ↩

- Leaving aside the question of particular political claims, this general feature of society in Trollope’s novels has been forcefully demonstrated in Ruth ApRoberts’s “Trollope and the Zeitgeist” ↩

- On Trollope’s contemporary reviewers, see Albert Pionke’s “Navigating ‘those terrible meshes of law.’” Examples of recent criticism on Trollope and the Law include Pionke’s article and Ayelet Bin-Yishai’s “The Fact of a Rumor: Anthony Trollope’s The Eustace Diamonds” as well as Jenny Bourne Taylor’s “Bastards to Time: Legitimacy as Legal Fiction in Trollope’s Novels of the 1870s” and Glynn-Ellen FisiChelli’s “The Language of Law and Love: Anthony Trollope’s Orley Farm.” ↩

- See Felber, 421-3 for a summation of the conflicting field of recent critical positions on this point. ↩

- My translation here sacrifices English fluency in the interest of preserving the parallel formulation of the German and its implicit invocation of Hobbes. ↩

- A fact also noted and elaborated on by Hall. ↩

- “godsend” is used both to speculate about money left in Lizzie’s accounts and to describe the role that the account of Lizzie serves in keeping the old Duke Palliser entertained. ↩

- For more on this latter point, see Psomiades’s discussion of Frank’s “final disgust at Lizzie’s physical presence” and Lizzie’s “untidy” lock of hair (111). ↩

- On this point, see Bin-Yishai, p.104-5 ↩

- As Trollope characterizes the “advanced buddhist” as worshipping a “hidden god,” we can infer that Trollope is less interested in developing any particular engagement with Buddhist religion than in opting to grab a convenient type from the cultural imaginary. ↩

- More precisely, Van Dam reads violence as structurally inherent in both positive and natural laws, but disagrees with Ben-Yishai that common law offers a meaningful alternative. I follow Van Dam in reading Mr. Dove’s opinion as proof of the ineffectiveness of common law as presented in this novel (807). ↩

- On this point, Lizzie serves as an excellent illustration of Hegel’s moral hypocrite – see Outlines p138-9 (Section 140), and his continuation of the argument relating hypocrisy to subject opinion, p144-5. ↩

Post a Comment